I used to ...

Mar 20, 2024

Nā Maxine Jacobs, he uri o Ngāi Tahu

I used to think being Māori was like being Christian.

I used to think being Māori was like being Christian.

I didn’t know a hell of a lot about the Bible or God – I still don’t – but in my mind being Christian meant following all the rules. Going to church every Sunday, reading the Bible, knowing the ins and outs of everything that I should or shouldn’t do to make sure I was doing “God’s work”.

Only by being the perfect Christian would I truly be a Christian. To know everything, believe fully, and stand up for all ideology – even if I found it to be against my own views. I thought I would only be able to call myself a Christian if I was fully versed and confident; anything less would be a costume.

It’s sad to think about that now. All the time I wasted thinking I would never stack up to this picture of what I had to be to be authentic. It was all in my head. No-one told me what to do or not to do. I created a set of rules no-one had written down, and told myself I would never be that because I didn’t fit x, y, or z.

Speak te reo, grow up on the pā, know haka, know waiata, know tikaka – I grew up knowing none of that. It’s actually unreal to think that I was literally eight kilometres away from Tuahiwi Marae and I was that disconnected.

It took me a long time to realise I was the person holding myself back. And back from what? The people who have been waiting for me to come and be a part of my community for years? The fear inside me that I wouldn’t stack up to expectations has been one I’ve carried around for a lifetime.

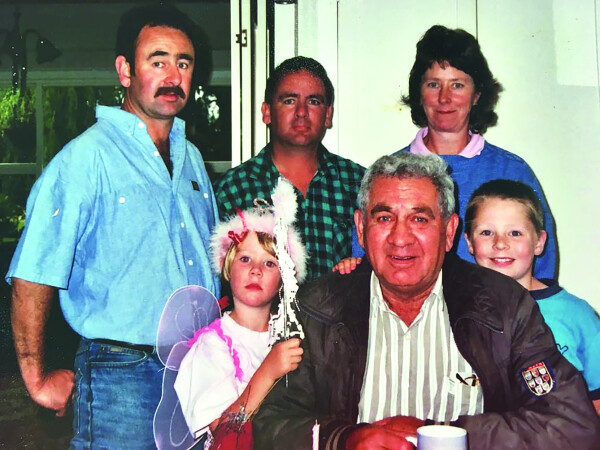

L-R: Uncle Clifford Jacobs, Todd Jacobs, Jenny Hart (Maxine's parents); bottom L-R: Maxine Jacobs (5 years), pōua Henry Jacobs, brother Isaac Jacobs (8 years).

I used to say I was Māori in my left hand.

I’d wave it when people asked, “What percent are you?” The skin on it is pink, just like the rest of me – it goes red if I stay out in the sun too long. This has been my biggest barrier. How could I be Māori if this is what I look like? It’s that stereotypical mindset again – this is what a Māori is, if you don’t fit that, you can’t claim it. .

I’m not too many shades away from my father, and all my cousins have the same skin. Well, the boys seem to tan better than the girls, but we could all pass as Pākehā if we wanted to.

I think this was a particularly important decision for me to make; do I pass as Pākehā only, or stand beside my whānau. Out at Ngāi Tūāhuriri I don’t know too many people yet, just the ones that live down Church Bush Road. For generations they’ve lived there, with more generations popping up as the years go on.

The question really came down to who am I going to be? Will I walk away from what my pōua helped to build up and preserve for our hapū because the pigment in my skin doesn’t speak for itself, or will I carve out a path to walk down that will empower me to feel comfortable in the skin that I was given?

I chose the latter. I spent this past year at a full immersion te reo course at Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato, walking down the first steps of that path. Every person in that class was a mix of different shades, different experiences, and different whakapapa, but they were just as Māori as the person sitting beside them, and just as Māori as me.

When I look at my hands now, they still look pink, but they don’t persuade me that I’m not enough. The idea of percentage doesn’t register with me anymore. People still ask me that question, “How Māori are you?” – with the inflection on the ā that I know we’re all too familiar with. Now I just give them my whakapapa. This is how I’m Māori; it’s an identity and a belonging, not a blood quantum.

Hukatai of Te Tohu Paetahi 2023 in front of Maungatapu Marae.

I used to be afraid to say I was Māori.

In my mind that would invite a whole raft of questions I wasn’t ready to answer. “What’s your marae called? Which hapū are you from? What’s your whakapapa? Can you speak Māori?”.

I wasn’t ready to answer those questions because I didn’t have the answers. To some of those questions, I still don’t. I was scared that if I didn’t have the knowledge, but shared my heritage, I would be questioned. And to be fair, I have been questioned over the years by Māori and non-Māori.

Because I can blend into the colonial side of Aotearoa, sometimes it was easier to not mention it at all.

I was worried I’d be seen as someone taking advantage of the turning tide, claiming my whakapapa when it became popular. A plastic Māori, if you will.

It wasn’t until a wise wahine looked me in the face and told me to grow up that I realised I was the problem. That was in 2018, and in the past five years I’ve taken steps – even if they were small to start with – to actually work towards breaking down my fears by learning what I can, where I can.

I’ve written stories and joined campaigns about te ao Māori as a reporter for Stuff, became its first Pou Tiaki reporter, visited Waitangi, started my learning journey of te reo Māori, gained a diploma in the language from the University of Waikato, and moved back home to Ōtautahi after spending six years away looking for something to bring home with me so I can feel like I deserve to return.

I can’t help but think of the quote, “knowledge is power”. It was probably meant in some kind of political schema type of way, but knowledge has given me the sword and the shield I’ve needed to keep walking forward.

But even now that I can rattle off the answers confidently, some people still find my whakapapa hard to believe. But it’s not my job to convince anyone who I am or where I’m from, as long as I know. That can’t be taken away from me, or anyone else.

Maxine on Waitangi's one-way bridge.

Now I believe I’m enough.

It’s been a long road for me to arrive at this belief. Looking back now, everyone who had already opened that door to their taha Māori didn’t view me as less. They were watching me through the window, waiting for me to open that door on my own terms.

Now that I’ve stepped through, I’m starting to see how much pain I was in on the other side. How much of myself I was holding back. In the class when we would do speeches every second week in te reo Māori, all that pain would come flowing out. To my embarrassment, largely through my eyes while I stood in front of 50 people, but they all knew what I was feeling.

I didn’t realise how being afraid to step into this world that’s been waiting for all of us was keeping me from being free.

It’s a strange feeling, like I’m looking at the same world, but it’s lit differently. It’s more vibrant and deeper than I understood, and there’s still so much more to learn.

I also didn’t understand that the values I had been raised in were Māori, but weren’t identified as such. The values of helping each other out just because we can, checking on our loved ones, being respectful to our elders and the environment. This is all manaakitaka, but I didn’t have the language back then.

What’s surprised me is how many people I’ve met along the way who feel the same as me. We’re held back by different things, have different fears, and struggle to know where to start. I thought there would be a perfect moment to start, a “right time”, but there isn’t. The time to start is when we’ve finally had enough, and begin walking through the door.

I don’t have to agree with everything my iwi does, or my hapū. My hand is not a scale of how Māori I am. My fear doesn’t hold me back. My knowledge does not define my birthright.

Ko au te whenua, ko te whenua ko au.