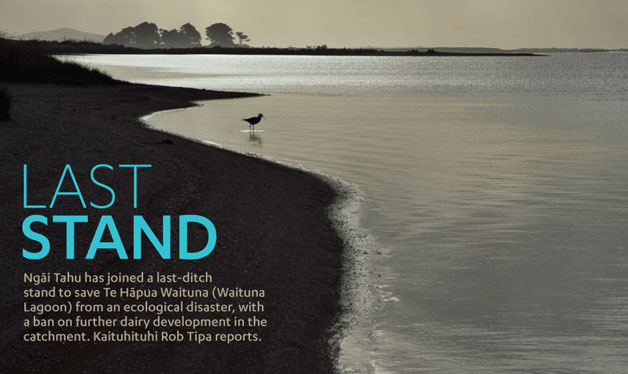

Last Stand

Apr 16, 2012

The Awarua-Waituna wetlands are among the last relatively unmodified expanses of wetlands left in Aotearoa, a delicate network of lagoons, estuaries, swamps, peat bogs, scrub and remnant patches of bush covering 132 km2 of low-lying coast between Bluff and Fortrose.

They were recognised as nationally and internationally important wetlands when New Zealand became a signatory to the Ramsar convention in 1976. The Department of Conservation (DOC) extended its protective umbrella over the lagoon when it declared it a scientific reserve in 1983.

Yet few Southlanders would argue that intensive dairy farming on the fringes of this catchment has caused a steady decline in water quality.

Historically, the wetland’s margins have been progressively cleared and drained to make way for more cows, more fertiliser and faster run-off of effluent, nutrients and sediment into the catchment.

In February 2011, a report from Environment Southland warned that nutrient levels were so high, Waituna Lagoon’s future hung in the balance and it was dangerously close to ‘flipping’ from relatively good health into a turbid and toxic algal soup.

For Ngāi Tahu, Te Hāpua Waituna is a taonga and a traditional source of mahinga kai, providing staple foods like pārera (grey duck), tuna (eels) and hao (a type of eel).

Te Ao Mārama represents the four Murihiku rūnanga – Ōraka-Aparima, Waihōpai, Hokonui and Awarua – on environmental matters. Te Ao Mārama resource management consultant Dean Whaanga (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu) says Te Hāpua Waituna is an outstanding waterway, a taonga of cultural significance.

To protect the lagoon, Awarua Rūnanga has announced a rāhui or ban on any further development of dairy farms in the catchment until the lagoon meets current guidelines on nutrient loadings.

While the rūnanga cannot impose or enforce the rāhui, it makes obvious the stance of the rūnanga on the issue. Rāhui is a traditional Māori tool to deal with an area under environmental stress.

“We’re aware there’s a problem with nitrate and phosphorus levels from the number of farms already there,” says Whaanga.

“Rather than adding to the problem by allowing more dairy farms and more cows in the catchment, we want to cease any more activity until they meet guidelines and targets set by Environment Southland and the Lagoon Technical Group.”

Consents for new dairy conversions had been deferred since last December until April this year, so effectively there has been a rāhui in place.

“We would like to leave the rāhui in place until the Lagoon Technical Group’s targets on nutrients, phosphates and nitrate levels are met and maintained.”

Whaanga says the rūnanga wants to protect the mauri (life force) of the lagoon. Any inappropriate use of its water diminishes its life force.

Awarua also wants more involvement in the management of water levels, specifically the decision on when to open or close the lagoon. Currently landowners have the right to do this without consultation with iwi or other parties involved in the wetland’s management.

And while the onus is currently on regional authorities to prove farming activities are harmful to the lagoon, Awarua wants farmers to take responsibility for their nutrient run-off and find their own solutions to problems. The rūnanga would also like to see riparian margins reinstated. It wants to create a buffer zone of at least 500m to 1km between the lagoon and farmland, to preserve the area’s iconic amenity values.

Te Ao Mārama, in partnership with Environment Southland, created the four-part “State of Southland’s Freshwater Environment” report, which covers health, ecosystems, uses and threats.

In September last year, they launched “Our Ecosystems”, which was reported in TE KARAKA Issue 51. That report says land use in Southland has intensified significantly over the past two decades, especially dairying and dairying support.

At the end of 2009 there were 589,184 dairy cows in the region, compared with 114,378 in 1994. The herds are farmed on just over 169,000ha of land. This land area has increased, by more than 10,000 ha since the 2008/09 season. The average herd size has also increased, from 365 in 1998/99 to 539 in 2009/10.

According to Fonterra spokesman Todd Muller, dairy farmers have made a significant effort in the past 12 months to build new fences, races and lanes, new effluent systems, ponds, and storage. They had fenced off bush blocks and planted riparian margins with native trees.

One farmer had spent over $100,000, and collectively DairyNZ and Fonterra spent over $1 million that wasn’t in their budgets a year ago.

“There is a commitment from the dairy industry to improve the situation and there is action behind the words,” Muller says.

Fonterra recognises the cultural and environmental significance of Te Hāpua Waituna to Ngāi Tahu and is committed to working alongside its suppliers to improve the state of the lagoon, he says.

Fonterra, Federated Farmers and DairyNZ had spent two or three hours on every dairy farm in the catchment to see how farmers managed their properties and to identify opportunities for immediate improvement.

“Above all else farmers need to take accountability for their own farms,” he says.

“We strongly encourage farmers to fence off streams. Ultimately it will be a condition of supply to Fonterra that by 2013/2014 all streams and rivers across the country, not just in Waituna Lagoon, will need to be appropriately fenced.”

There are nine criteria required for wetlands to meet international standards, and Waituna meets seven of those nine requirements.

Scientists are concerned about losing two keystone species of Ruppia (seagrass) and other aquatic plants in the lagoon, which play a critical role in maintaining water quality and stabilising sediments. They have established 48 monitoring stations in the lagoon since 2009 to establish how abundant and widely distributed these plants are.

DOC wetlands ecologist Dr Hugh Robertson says they have noticed a large decline in aquatic plants over two-thirds of the lagoon in the past year. However, in a rare piece of positive news for the catchment, Ruppia and Myriophyllum species have bounced back this summer with an extensive flowering season.

“Part of the explanation for that is the opening regime, which is a really critical part of the system,” he says.

Essentially the lagoon was opened to flush out nutrient-laden water and algae, completely changing water levels, reducing salinity and improving growing conditions for aquatic plants. While water temperatures in the lagoon are still warm and nutrient levels are high, phytoplankton levels were low in early February.

Environment Southland scientists acknowledge the risks of leaving the lagoon closed during a hot summer, but they believe maintaining freshwater conditions is helping aquatic plants to recover, protects the ecology and reduces the likelihood of the lagoon “flipping”.

Environment Southland chairman Ali Timms says the council had to act quickly in February last year when it learned of the threat of the lagoon “flipping into a toxic and turbid algal soup” but acknowledges there has been criticism of its efforts.

“Some of the community saw our response as too slow, but it was essential that any actions taken to save Waituna would actually work.”

“They needed to be based on sound science and to respect other people’s rights. It’s a complex system and we needed more knowledge of interactions within the lagoon and of surrounding catchments.”

Negative publicity in the media had meant an “ugly” winter for dairy farmers in the Waituna catchment but the farming community was willing to get actively involved and be part of the solution, she says.

Waituna farmers, with DairyNZ and Federated Farmers, have prepared farm action plans that have resulted in 100 per cent compliance with Environment Southland’s rules.

Environment Southland is currently reviewing all consents in the catchment to ensure that effluent discharge systems are efficient, effective and comply with discharge plan conditions. Many farmers had proactively sorted improvements well before those consents were reviewed.

But the council wants more financial assistance from central government and the dairy industry, both natural funding partners. Ali Timms says financial responsibility cannot be carried by ratepayers alone.

“Saving Waituna is the top priority for Environment Southland councillors, who are 100% behind that.

“We can’t do it alone. We need the support of everyone to save the lagoon.”

At a public forum on Waitangi Day this year, Awarua Rūnanga ūpoko Tā Tipene O’Regan told visitors to Te Rau Aroha Marae in Bluff that the ecological health of Te Hāpua Waituna was close to the core of tribal health.

The rūnanga took great pride in the range of kaimoana (seafood), including tuna (eels) and Bluff’s famous tio (oysters), it laid out for 200 or 300 guests visiting the marae on Waitangi Day.

“If we didn’t have wetlands like Te Hāpua Waituna, we wouldn’t be able to put these foods on the table. It’s not just about restoration of Mother Nature. These principles are a central component of who we are as a people.”

Tā Tipene says Ngāi Tahu has gone to a lot of trouble to protect customary rights as guaranteed under the Treaty of Waitangi and it is important to continue to exercise those customary rights and mana over tribal taonga such as Te Hāpua Waituna.

Ngāi Tahu also negotiated a statutory acknowledgment of the tribe’s rights and interests in the Waituna Lagoon within the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act, highlighting the significance of the wetland complex to Ngāi Tahu.

“The ecological health of our environment is fundamental to our being able to exercise our customary rights. We see it as a treaty issue and in everyone’s interests that our water is clean.

“We’re not saying we want to inhibit dairying – we’ve just got to do it better and look after the health of our rivers and coasts.”