Lifeblood of the valley flows again

Dec 21, 2021

Along the southern edge of the Lower Waitaki River, a team of kaiaka taiao, or indigenous rangers, have been hard at work clearing scrub, establishing native plantings and monitoring an extensive network of traps. Whiria Te Waitaki is a restoration project led by Te Rūnanga o Moeraki, weaving together aspirations for the health of the catchment, and creating career opportunities for their whānau. Delivered in partnership with Toitū Te Whenua – Land Information New Zealand (LINZ), Whiria Te Waitaki is funded through the Jobs for Nature COVID-19 recovery package.

Kaituhi Anna Brankin reports.

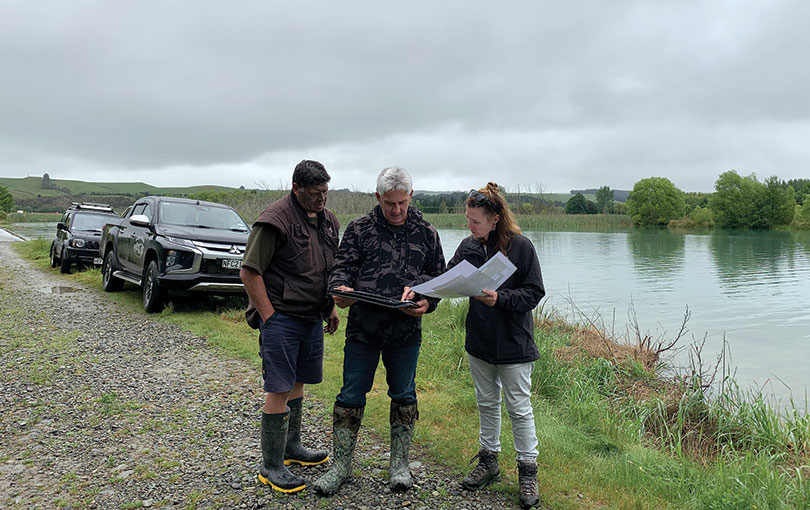

Above: Whiria Te Waitaki rangers Mauriri McGlinchey, Patrick Tipa and Kauri Tipa at Te Puna a Maru, one of two sites they are working to restore.

Once known for its thriving pā and nohoanga, mahinga kai and well-trod migratory trails, the Waitaki Valley is now largely agricultural. Pasture grass and grazing sheep and cattle dominate a landscape once dense with native bush, and the braided floodplain has been severely impacted by the physical modifications of the Waitaki Hydro Scheme. Riparian wetlands and shingle river beds have been damaged and destroyed; those that remain are overgrown with invasive plants and overrun with predator species, endangering the habitat of native birds, fish and invertebrates.

For generations, private land ownership has made it nearly impossible for manawhenua to access these sites and fulfil their role as kaitiaki – until now. Upoko of Te Rūnanga o Moeraki David Higgins describes Whiria Te Waitaki as the realisation of a longheld dream, the culmination of decades’ worth of work to see the river restored to its rightful role as the lifeblood of the valley.

“It was years ago that I first worked with the late Kelly Davis and many of our pōua and tāua to gather evidence for the Ngāi Tahu claim about the awa, and I am privileged now to see our aspirational dream realised, of having our footprint once again well established,” David says. “We look to the Waitaki, or as we call it, Kā Roimata o Aoraki, as the embodiment of ki uta ki tai, from the mountains to the sea, as the understanding of the whakapapa of our environment and how everything is part of the whole.”

The name Whiria Te Waitaki – braid together the Waitaki – is a play on words, referencing the distinctive braids of the awa itself, as well as the way the project brings together the inextricably linked elements of water, land and people. Project lead Dr Gail Tipa (Ngāi Tahu – Moeraki) says that these individual threads have been longheld aspirations for the rūnanga.

“The idea started off as an indigenous ranger programme: getting a team of our people visible in the takiwā and working in a way that represents our values, and at the same time providing employment pathways for whānau,” says Gail. “That led to a conversation about what these rangers were going to do, and that’s when we reframed it as a restoration project – restoration of our presence, on a kaupapa that resonates with us, at sites that are significant to us.”

In mid-2020, LINZ sought applications for joint agency projects that would boost regional employment and progress environmental outcomes. Te Rūnanga o Moeraki submitted a successful application, securing funding for the project until June 2024. In total, Whiria Te Waitaki seeks to create at least nine jobs, and allow the rūnanga to progress the restablishment of native habitats and mahinga kai in the catchment.

Work is already underway on 375 hectares of Crown land across two culturally significant sites. Korotuaheka, at the mouth of the awa, is where Te Maiharoa established his settlement and where he still rests in the urupā. Te Puna a Maru, located in the middle of the valley, was a thriving pā until the late 1800s and the home of rangatira Te Huruhuru.

“Kelly Davis and I were fortunate enough to have grown up with the old people who knew those places well. We had to revive those memories, so that our Whiria team could understand the reason those places were selected,” David explains. “We had to restore the mana so that our team could go up there with comfort and confidence that they know the history and traditions associated with those places.”

Whiria Te Waitaki also encompasses ongoing collaboration between the rūnanga and local landowners to implement farm planning initiatives that will mitigate environmental impacts of agriculture

“The kaupapa is so meaningful from the point of view that it’s creating access to mahinga kai

that has been inaccessible for generations. From a cultural perspective, from a hauora perspective, from a wairua perspective, this project is achieving so much and laying a foundation that will

allow our whānau to reintegrate, reconnect and reassert ourselves in the Waitaki.”

Justin Tipa Te Rūnanga o Moeraki chair

Te Rūnanga o Moeraki chair Justin Tipa says the impact of Whiria Te Waitaki cannot be underestimated. “The kaupapa is so meaningful from the point of view that it’s creating access to mahinga kai that has been inaccessible for generations,” he says. “From a cultural perspective, from a hauora perspective, from a wairua perspective, this project is achieving so much and laying a foundation that will allow our whānau to reintegrate, reconnect and reassert ourselves in the Waitaki.”

That foundation is being laid one day at a time by lead ranger Patrick Tipa and his team Mauriri McGlinchey, Kauri Tipa and Kyle Nelson. All four are Moeraki whānau, and with more rangers expected to join their ranks next year, as well as opportunities for Moeraki contractors, Whiria Te Waitaki is certainly delivering on its intention to provide employment.

The model provides ample opportunity for career progression and succession planning, with existing rangers selected for their broad range of age and experience. “In the case of someone like Patrick,

it’s about allowing him to develop and express his leadership abilities with confidence,” says David. “On the other end we have young Kauri under our wing, and the opportunity to mould him, give him the skills and work ethic, and a huge source of pride in what he’s doing for his people.”

Above: Leader ranger Patrick Tipa discussing a predator control plan with local contractor and Moeraki whānau member Joe Taurima (Mana Wild Game Solutions) and Whiria Te Waitaki project manager Kelly Governor.

The kaiaka taiao, or indigenous rangers, are distinct from traditional Department of Conservation (DOC) rangers in that they are reviving generations of mātauranga Māori and whānau values in the work that they do, with the full support of the rūnanga. “Growing the cultural capacity of our people is a big component of this mahi,” explains Justin. “Yes, they’re learning the technical skills of the job, but they’re also learning the whakapapa, the karakia, the reo. They’re not just rangers – these are people that will be our mātanga mahinga kai, our mahinga kai experts.”

The rangers themselves unanimously agree that Whiria Te Waitaki is the opportunity of a lifetime, allowing them to be in meaningful employment within their own takiwā. Patrick had already made the decision to return to Moeraki several years ago, but was uncertain whether this commitment would result in a permanent role in the area, or whether he’d have to continue spending periods of time away doing contract work.

“It’s pretty amazing really. For several years now, we’ve been having discussions about getting things happening at Moeraki and creating jobs,” Patrick says. “And now it’s actually come to fruition, when people can actually come home and work in our own takiwā. That’s everybody’s dream, isn’t it? To actually do mahi on your own whenua, your own awa.”

Mauriri agrees, saying that after living in Australia for a number of years he’d been waiting for the opportunity that would finally bring him home. It was Covid-19 that brought him back to the country, and Whiria Te Waitaki that brought him back to Moeraki. “The fact that I was able to come home and get meaningful mahi around my people, around the marae – I couldn’t ask for much more really,” he says.

“I think I’ve landed a pretty sweet job, considering, so I’ve put myself down for the next 20 years. I reckon there’s enough mahi to keep me going, so I’ll stick around.”

“It’s pretty amazing really. For several years now, we’ve been having discussions about getting things happening at Moeraki and creating jobs. And now it’s actually come to fruition, when people can actually come home and work in our own takiwā. That’s everybody’s dream, isn’t it? To actually do mahi on your own whenua, your own awa.”

Patrick Tipa lead ranger

Meanwhile, 17-year-old Kauri ended up taking a role as junior ranger when he found himself at a crossroads in terms of deciding whether to head back to school, seek employment or get a professional qualification. “My dad told me that a job was coming up, that it was up the Waitaki, and that it would be with whānau,” he says. “I was really keen on getting out and about doing all the environmental stuff, so I moved down to Moeraki and now I’m working full time. I reckon it’s amazing, to be honest, I don’t see many kids my age doing this, especially working with the whānau in their own rohe.”

Within a few months, Kauri graduated to a role as a fully-fledged ranger, and says that the skills he has learned have set him up for what he hopes is a long career in environmental restoration. “I’m really thankful that I got this job, it’s just wicked eh. I really want to do this long-term, working as a ranger all around the country.”

The programme of work carried out by the team includes improving access to Korotuaheka and Te Puna a Maru through track development, robust predator and weed control, seed collection, propagation and native planting, and cultural monitoring of native birds, fish, plants and invertebrates.

“The boys kicked off by sourcing our own seeds from the old native stands that are still left in North Otago,” says Patrick. “We propagated them in the tunnel houses that the rūnanga already owned, and we’ve now got two and a half thousand native plants grown from seeds we collected.”

Above: Rangers Kauri Tipa and Mauriri McGlinchey prepared to get stuck in for an afternoon of clearing scrub.

Patrick says that as well as learning the new skill of propagation, it’s significant to be able to incorporate mātauranga Māori into the process. “We’ve been learning the Māori seasonal changes, which has been quite exciting, and every new plant we grow we’re making sure to know the Māori name as well as the Latin. It’s about finding ways to put a Māori lens on everything we do.”

Over the winter, the team spent time refining their building skills, constructing 130 double set DOC-200 trap boxes, before placing them in a network throughout Korotuaheka and Te Puna a Maru that will bring down rat, stoat and hedgehog populations. Now, they’re focusing on clearing space for new plantings and creating access points into the more overgrown parts of the sites.

For Gail and the rest of the steering group, it’s a matter of pride to see years of planning and dreaming being realised in the work of Whiria Te Waitaki. “I’m so proud and chuffed with the rangers, and the mahi that they’re doing,” she says. “To know that our team are out there, honestly it’s just a wonderful feeling. Throughout my career I’ve done countless submissions and resource consents, but seeing what these guys can do on the ground is one thing that I’m really proud to have contributed to, in some small way.”

“I’m so proud and chuffed with the rangers, and the mahi that they’re doing. To know that our team are out there, honestly it’s just a wonderful feeling. Throughout my career I’ve done countless submissions and resource consents, but seeing what these guys can do on the ground is one thing that I’m really proud to have contributed to, in some small way.”

Dr Gail Tipa Project lead

As Justin explains, it’s not just about the environmental restoration that the rangers are carrying out along the awa – it’s also about the restoration of a Moeraki presence. “It’s about being kanohi kitea in the valley, having our team on the ground, interacting with landowners, putting our narratives back out there,” he says. “They might pull up in a town to get lunch and people notice the logo on the truck and their uniforms and say, ‘who are you guys, what do you do?’ And we’re finding that there is a good degree of support from the wider community – when people engage with our kaupapa and understand it, they want to be involved with it.”

That presence is of incredible importance to the wider rūnanga, who have not been accustomed to seeing themselves so visibly accepted within their own takiwā. “It is with delight and some pride that I look at those rangers dressed up in their gear,” says David. “When they’re out in the community, or here at the marae when we have groups visiting, it’s a huge matter of pride amongst our whānau.”

On behalf of the rūnanga, Gail speaks highly of the relationship with LINZ, and is careful to acknowledge the many people who have been involved in bringing Whiria Te Waitaki to life.

Above: Waitaki River.

“Our rangers themselves are stunning, we were lucky to pick up a project manager in Kelly Governor, we have a project steering group that brings together a truly diverse skillset, and Aukaha has enabled us to actually deliver on the contract and all the administration that comes with it,” says Gail. “And we are just so lucky to have found a new partner in LINZ, and to have this blossoming relationship.”

Although the initial funding is for a duration of three years, Te Rūnanga o Moeraki hopes to continue Whiria Te Waitaki in perpetuity. “We’re working hard to secure the funding and the longevity of this kaupapa,” says Justin. “We’re actively looking to partner with other groups in the community like irrigation companies, or directly with landowners. Whiria Te Waitaki is our chance to put a stake in the ground and show our people what’s possible, that we can offer viable careers at the pā.”

When thinking about the long-term impact of Whiria Te Waitaki, it’s Kauri who is the most likely to see it through. As he stands at the edge of Te Puna a Maru, gazing out at the section they’re just beginning to clear and plant, he says: “you look at that now and it’s just chocka with gorse and scrub. But in 20, 30 years time, it’ll be completely native species. There’ll be walkways through here, so our whānau can come here and actually access the site, and enjoy being back in our own places again.”