Money Matters10 Years of Whai Rawa

Sept 30, 2016

In 2001, a little-known charitable trust was formed in the belief that tertiary education should be for everyone. That trust lobbied two of Helen Clark’s governments to form an education savings fund – a concept that was canned indefinitely just days after Clark led a third Labour victory in 2005.

Rather than following the state’s example – and opting for student debt over savings – Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu leaders saw an opportunity to provide their people with increased access to tertiary education, home ownership, and retirement support. And so Whai Rawa was born.

Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri, ā muri ake nei – for us and our children after us.

Kaituhi Arielle Monk reports.

Tā Tipene O’Regan with then Finance Minister Michael Cullen at the Whai Rawa launch in 2005.

From the time of enterprise and trade with Europeans in the very early 19th century, to the unstoppable generations behind Te Kēreme, Ngāi Tahu has been trailblazing, caring less for following and more for leading – often into the unknown.

It was with this cultural precedent that former Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (TRoNT) CEO Tahu Potiki set about laying a path of indigenous corporate responsibility for the iwi businesses.

“I really did think that we had to figure out how to get money out of the building and into the homes of Ngāi Tahu people – every single one of them,” Potiki says. “That was my objective.”

The first Potiki heard of a tertiary education-focused saving fund, he had been slung a hook by his then-father-in-law Tā Tipene O’Regan. Too busy at the time to take the invitation, he had referred Potiki on to a contact in The New Zealand Institute, a self-funded ‘think tank’, now merged with the Business Roundtable to form the New Zealand Initiative. The New Zealand Institute’s interests lay with the development of socio-economic policy, among other issues. At the time, the institute was investigating the rising costs of tertiary education and the barrier this presented to people pursuing further education.

“Tahu became particularly enthused by this [idea of a savings scheme],” Tā Tipene says.

“Right through the settlement process, we were looking at ways and means to be of benefit to our people.”

The actual logistics of distributing the wealth to enable such benefits, however, were complex: infrastructure was essentially required from the ground up. The year was 2001, and TRoNT and its subsidiaries were making quick work of intelligent post-settlement investment – a lot of money was being made, but not a lot was being distributed among the tribe.

By a stroke of luck, voluntary and private sector finance guru Diana Crossan had been pulled into the discussion of rising student debt and falling Kiwi savings, and was leading the debate with a small charitable trust known as FUNZ. In late 2001, FUNZ began touring the country to research the problems posed by mounting student debt, with particular attention to Māori.

“Here, it was Tahu who was the most interested, and then Tipene became involved,” Crossan says. She presented her ideas at a first meeting with Potiki, uniting the FUNZ and TRoNT interests to promote furthering education. The organisations kept in touch. Despite setbacks to FUNZ’s efforts on a national stage, in the mid-2000s TRoNT had already independently begun to research a viable channel for the exact scheme the government was rejecting. In 2005, Kaiwhakahaere Mark Solomon asked Crossan – who had then been the Retirement Commissioner for two years – to chair the Whai Rawa Trust.

“They called me up and asked me to be on the board, and I thought, ‘Why not?’”

The Whai Rawa Trust was born, and pulled alongside Crossan to govern it were Tā Tipene and former finance minister, David Caygill. Caygill asserts he was there to tell stories, Tā Tipene was there to keep them ethical, and Crossan was there to “put them to work”.

“It was a pretty revolutionary thing in its day, even more so than the KiwiSaver concept,” Tā Tipene adds, with perhaps a hint of pride at the foresight of the iwi – Whai Rawa was a calculated punt ahead of even the political powers of the time. “But there were various questions posed – one of them was that this was a benefit being distributed to a section of our people, and not to others.”

“I think what’s appealing about it is having somewhere that is committed to saving. And you’re doing that alongside your brothers and your sisters, and your cousins. Anybody can save into a bank, but not everybody gets an opportunity to save along with their tribe.”

David Tikao

Whai Rawa Programme Leader

By this, Tā Tipene refers to the fact that about half of iwi members have set up Whai Rawa accounts – so what about the other half? That is an issue Whai Rawa Programme Leader David Tikao is constantly confronting in day-to-day operations with his team.

“We’ve got a glaringly obvious gap in our membership … it’s thesame gap that appears across multiple standards in New Zealand. I think we are already making a difference – we’ve got around 5,000 rangatahi in Whai Rawa. But there’s still around 15,000 that we haven’t got to.”

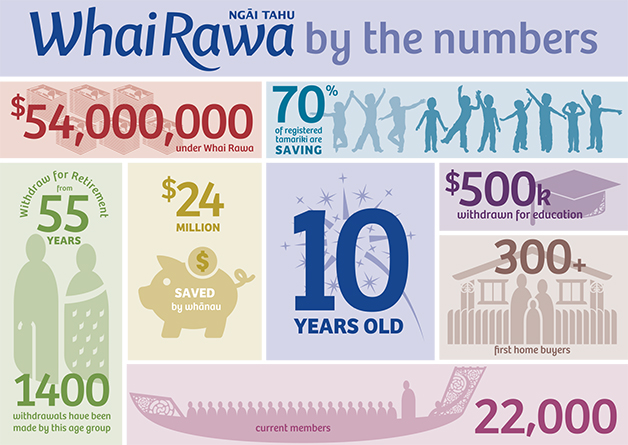

As it operates today, Whai Rawa offers matched savings – up to $200 annually – at a rate of 4:1 for members under 16, and 1:1 for members aged 16–65. A distribution of profit funds, set by TRoNT annually, is also paid out at the end of the financial year and newborn Ngāi Tahu pēpi registered with the scheme receive a one-off $100 boost. Funds can be withdrawn at the completion of a tertiary qualification to assist with student loans, to contribute to a first home loan, and after the age of 55 to support retirement.

And although access to opportunity through long-term saving is the key to the scheme, Tikao is thoughtful about the capabilities of Whai Rawa and believes that through “empowering whānau to choose to save”, they will benefit from more than just the dollar value.

“I think what’s appealing about it is having somewhere that is committed to saving. And you’re doing that alongside your brothers and your sisters, and your cousins. Anybody can save into a bank, but not everybody gets an opportunity to save along with their tribe,” Tikao says.

“The investment the tribe is making in you, and your future – that’s a big part of it too.”

Tikao has been on board for five years, returning home from London to take up the role. He would often get a snippet of iwi affairs via TE KARAKA on the tube commute, acutely feeling the fact that he was one Māori among hundreds of people. Here, he is but one feather in a very large, very rich cloak.

The Whai Rawa administrative unit took on another staff member recently. New legislation brought in by the Financial Markets Authority has added what equates to a full-time role to look after legal obligations. The legislation, designed to ward off money laundering and fraud, comes into full effect this December and will establish Whai Rawa as a licensed Managed Investment Scheme. Tikao says that, despite the extra costs and work now involved in running the scheme, the license is a boost in credibility for Whai Rawa.

On its 10th anniversary, the victory and the evolving organism that is Whai Rawa should be celebrated. But it is apparent to all concerned in the stewardship of the scheme that there is more work to be done.

Although he champions the scheme, Tā Tipene acknowledges there are further costs that occur in life. And it’s something that TRoNT itself is facing, as the astute post-settlement business and investment continues – how else will the vast profits be distributed?

“Whai Rawa is great. But it’s only one of a suite of distributional devices that we use, and I do think we need to think more creatively about how we go beyond this initiative.”

David Caygill says the mean number of dollars by contributors is one to watch, to ensure it is always increasing, never lagging or falling. That average amount of savings has risen from under $1000 during his early days on the board to $2,375, and will continue to climb as scheme members develop stronger savings habits.

David Tikao sees the need to further reach whānau to increase membership in the scheme from the current 52% of all registered Ngāi Tahu. The primary benefit of increased uptake is, of course, wealth distribution. The secondary benefit is also vital: encouraging individuals to plan for a brighter future one way or another. “There is something for everyone”.

If there is one thing the voices of the foundation, support and management for Whai Rawa agree on, it is Potiki’s initial assertion. “It has the potential to improve quality of life.”

Rangatahi carve a place in the world

Toya Woodgate.

Better access to tertiary education for the people is arguably at least one of the driving catalysts that began a conversation around Whai Rawa’s inception in the early 2000s.

Although some would say New Zealand tertiary education is highly accessible via the government agency StudyLink, the average Bachelor’s degree from an accredited tertiary provider will cost at least $18,000 over three years. This considerable chunk of debt does not include the costs of life’s essentials like housing, food and transport.

In 2014, 186,477 students racked up $1.6 billion in debt – an average of $8,580 each.

So it isn’t a stretch to surmise the trade-off for tertiary education is a sizeable millstone called the student loan. Whai Rawa was born with the specific intention to encourage Ngāi Tahu whānau to save long-term and allow those savings to be withdrawn at three stages over a lifetime. The first being at the completion of a tertiary qualification – paying back student debt.

The Whai Rawa programme leader himself has made a withdrawal to ease the burden of student debt. Thanks to his Whai Rawa savings, David Tikao is just two payments away from clearing his loan entirely.

Tikao completed an Executive MBA through Massey University; his look of relief at the debt reduction is palpable. “It took out a nice big chunk for me.”

For most making that first withdrawal for further education or training allows them to save for the next potential withdrawal: a first home purchase.

Toya Woodgate, 22, is an early childhood teacher.

As an employee of Te Rūnanga, Toya’s mum joined her tamariki up to Whai Rawa 10 years ago. At 17, Toya began working casually for the iwi office herself and learned the value of the saving scheme up close while processing administration for the unit.

She graduated last year from the Canterbury College of Education with a Bachelor of Teaching and Learning with First Class Honours. She now teaches at Hoon Hay Primary School.

In December, 2015 Toya and partner Callum McKenzie began looking around at viable first home options. They were astounded at the real estate market and were quickly forced to look outside Christchurch. Five months later, the Selwyn district became their hunting ground and after several false starts, with frustration mounting, the pair resorted to TradeMe. Within minutes, they found a house that ticked the boxes, arranged a viewing and put in an offer within five minutes of setting foot inside the door.

Although “stressed out” by the purchase, with support from Callum, her whānau and the Whai Rawa team, Toya was able to use her account balance as part of the settlement deposit on the Leeston property.

“I had had all my Whai Rawa withdrawal applications ready to go from December. The staff there really helped me calm down!

“I wouldn’t have been able to afford to buy a house without that extra amount there, and the bank probably wouldn’t have supported us as much financially either.

“It’s funny, we were talking the other night and it still seems like a dream,” Toya says, speaking down the phone from the comfort of her very own home.

Pēpi to Pōua, Toddler to Tāua

Riana Bennett with Maia, Ryan and husband Jeremy.

There were different priorities before motherhood but, after two tamariki, there was suddenly a more concrete long-term future to plan for Riana Bennett (Ngāi Tahu – Makaawhio, Ngāti Māhaki).

“It’s my main goal now to provide for my kids. Before them, it was all about me and ‘What am I doing Saturday night’ – but now in all our financial aspects and aspirations, we’re looking towards the kids.”

Whai Rawa enables her and husband Jeremy to do just that – with ease. Ryan, 4, and Maia, 1, are both registered members of the iwi and Whai Rawa. More than 70% of Ngāi Tahu children registered are already saving, and every pēpi signed up by parents before their first birthday is gifted a $100 kick-start into their account.

Riana says the administrative side of signing up can be a barrier for whānau, but the Whai Rawa applications are well worth it in the end.

“I don’t want them to have a financial burden if they want to study something amazing … if I can provide that for my kids, it means that when they go to buy their first home there will be money sitting there.

“As soon as they were born, we set up bank accounts for them, we got their IRD numbers sorted and they have their Whai Rawa accounts. Actually, the kids have more money than me!”

Riana has been a member of the iwi saving scheme since it began in 2006, and hasn’t made a withdrawal to date.

“[It’s for] retirement, absolutely,” she says, nodding.

Her grandparents lost faith in saving schemes after money they invested in 1975 was effectively wiped under Robert Muldoon’s government. The money was never returned.

“And they have had financial challenges because of that. I don’t want to be struggling, so we’ve thought, ‘What can we do now and in the next 30–40 years?’

“My beliefs are that I have my faith and trust in Ngāi Tahu.”

Wiremu Rickus (Ngāi Tahu, Arowhenua, Ngāti Raukawa) couldn’t agree more.

As a member of Whai Rawa for seven years, all of those after the age of 55 when a kaumātua can withdraw, he knows well the value of the iwi investment. He can’t quite remember why he signed up, but he is glad he did.

“I thought, ‘yeah, may as well’. It’s a Māori kaupapa, it’s the whānau, which I like.”

He has withdrawn from his account a few times in the past few years. His elderly mother, still living in Horowhenua where he grew up among Ngāti Raukawa whānau, is suffering from advanced dementia. To help her carer provide quality of life, he purchased a car for her. His aunty, who lives two houses away, drives her to the shops and around the Horowhenua district.

“It’s been very stressful for us, the whānau. I know I’ve spent a bit on her but it’s been about trying to get our mum settled,” Wiremu reflects.

He has also withdrawn after answering the call home and expected to find his mother on her deathbed. And he did – but she made an unexpected recovery – a “false alarm,” Wiremu chuckles.

Although a serious stroke forced him from his job as a bus driver five years ago, he still religiously contributes to Whai Rawa from his income at the Lincoln GoBus service bay. He works 4.30 pm–1.00 am servicing buses as they come and go, until the last has finished its route –Tuesday through Saturday.

“It keeps me motivated and fit. We may be at the bottom, but like the old saying goes, when things are right in the back, things will be right in the front.”

Wiremu, 64, is hoping GoBus will expand further in Wellington; a transfer is high on his mind.

“I’m missing my family up north. I miss my sons and my daughter.”

His three grown children live in Taupō, Hamilton and Hawke’s Bay respectively, and he has 11 mokopuna and two great-grandchildren. Does he think he’ll go back?

“Oh definitely, definitely. I miss them so much, it’s hurting me here,” he indicates to his heart.

And when the time comes for his big move, he knows his Whai Rawa account will stand him in good stead to realise the dream of returning to his northern whānau.