Reconnection - a life-long desire

Aug 5, 2024

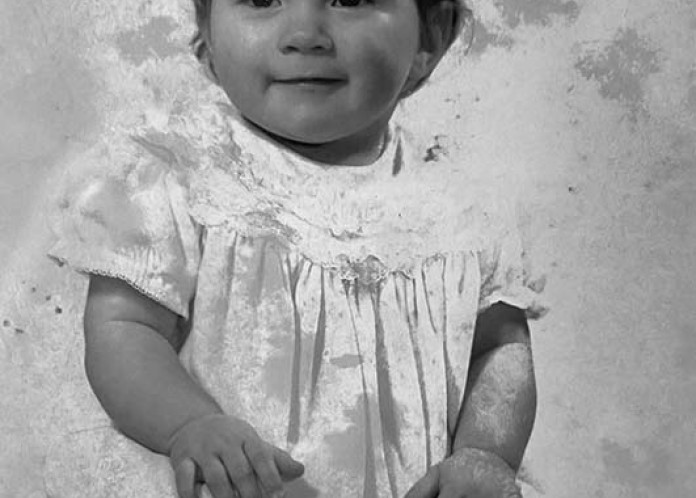

Image: Friedlander Foundation creative director Jillian exudes the warmth and vivaciousness for which she is well known. Photographs: supplied

Image: Friedlander Foundation creative director Jillian exudes the warmth and vivaciousness for which she is well known. Photographs: supplied

Although she’s lived in Tāmaki Makaurau for more than half her life, Jillian Friedlander is still a southern girl at heart. The warm and vivacious Creative Director of the Friedlander Foundation sits down with kaituhi Anna Brankin to reflect on her childhood, her family and career, and shares a yearning to reconnect with her roots.

“My husband Daniel likes to say that I’m the only woman he knows who can hunt, fish, skin a possum and still wear a pair of heels,” Jillian says. It’s been nearly 30 years since she moved away, yet her upbringing in the heart of Murihiku has left an indelible mark.

Jillian and her sisters cultivated a deep connection to the land

during their childhood, moving around between the Catlins, Waihōpai and Ōtepoti. Although she didn’t realise it at the time, the family’s Kāi Tahu whakapapa had a strong influence on their way of life. Jillian has a formative memory of being four years old and riding on her dad’s shoulders in the dark during a muttonbirding trip down on Whenua Hou.

Her parents never used the term mahika kai to describe their food gathering practices, but that’s what they did. “We’d go to Oreti Beach to get tuatuas, or Dad would go out and get pāua and our job as children would be to get the old-fashioned hand grinder and mince it all up to make the patties,” she says. “Someone would get a sack of oysters from Bluff and all the uncles would come around. They weren’t actually uncles, but that was how things were, especially when someone had oysters. One for the pot and two for the belly.”

“We learned about the different trees and flowers in the bush, and the uses for them. My great granny, she was based in Mataura, but she’d grown up in the MacLennan and knew about bush medicine. So we always knew how to identify the pepper trees, and how to check the bark on the trunk of a rātā to figure out which way was north.” Jillian Friedlander

There were plenty of hāngī, with the kids helping out with the digging and pulling sacks over before sitting on upturned beer crates to wait for their kai … the house was always full of music.

With three daughters, Jillian’s dad quickly got over any notion of what girls should or shouldn’t do. “We didn’t really get much choice in the fact that we’d be going out hunting and fishing, and playing rugby with the other kids,” she says. “Church on Sunday was about the only time we wore skirts or dresses.”

The whānau spent a good chunk of Jillian’s childhood on a farm near MacLennan, in the Catlins, where she and her sisters had 300 acres of native bush to explore. “We learned about the different trees and flowers in the bush, and the uses for them. My great granny, she was based in Mataura, but she’d grown up in the MacLennan and knew about bush medicine,” Jillian says. “So we always knew how to identify the pepper trees, and how to check the bark on the trunk of a rātā to figure out which way was north.”

Although she loved her upbringing as a “bush kid," Jillian knew from a young age that her life’s trajectory would take her away from Murihiku. “There was a creative streak in the family that I inherited. I was always involved in colour and music, and I had this grand dream of going to Paris to be a creative.”

After studying art history at university, a stint in hospitality in Queenstown and some overseas travel, Jillian found herself in Tāmaki Makaurau, helping her sister out with her newborn baby.

“I was 23 and felt so adult, but I was just stumbling around really. That was when I met my husband and, as they say, that was that.” Daniel’s family runs the Friedlander Foundation, a private philanthropic trust that supports initiatives under three main pillars: the arts, youth development and medical sustainability. Jillian was immediately drawn to the first pillar, seeing the chance to put her lifelong interest in the arts to good use. “After joining the Friedlander family I observed a lot from the sidelines, and the biggest thing I learned was about equal opportunity,” she says. “All of our projects are about giving equal opportunity and having an impact. It’s not just a feel good thing – it has to actually make a difference.”

Jillian is now Creative Director for the Friedlander Foundation, and is proud to have led several projects that foster new talent and create opportunities for artists – from sponsoring budding opera singers and ballerinas to funding The Lullaby Project, a kaupapa run by Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute in which professional artists support teenage parents to write personal lullabies for their babies.

“I also considered it imperative that we do something for Māori artists, and that’s why we came up with Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa,” says Jillian. Established in 2020 in partnership with Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi, Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa is awarded annually to a Māori or Pasifika artist. It celebrates and uplifts the innate creativity of Māori artists and supports their ongoing work with a $30,000 award. To date we have partnered with two Ngāi Tahu artists – Ariana Tikao and Dr Areta Wilkinson.

Creating this award was something of a milestone for Jillian, who has not always found it straightforward to celebrate her own identity as a wahine Māori. In part, this was because she didn’t know much about her whakapapa. “My mum and dad were quite isolated from their families. My dad’s father was killed on the farm in an accident and my granny remarried quite quickly and moved away. “Meanwhile, my mum was adopted. We were able to track her birth mother eventually but all we know about her birth father is that he was referred to as the ‘half-caste’.” Unfortunately, it was common for Māori whānau to conceal their heritage in those days to avoid prejudice and better assimilate into Pākehā society. Excuses were made for family with darker colouring, including Jillian, who grew up hearing the story that she was so olive at birth that she was almost mixed up with another baby at the hospital. “It just wasn’t spoken about. The older generation would say ‘it’s just a little bit of Italian in the family’, and I was always told that I was a throwback, or that I’d been touched with the tar brush. That was a classic one, so I internalised that. It’s not that I was ashamed to be Māori, but I was cautious.”

These attitudes left Jillian with a sense she had to wear a mask to conceal her true identity, and only recently gained the confidence to shake it off. “I just had to take it on the chin and I couldn’t make a fuss about it. That’s why I talk about the masks we all wear. It’s not that you choose to wear them, because it bloody hurts. I’ve basically laid mine off now.”

Over the years, Jillian has become increasingly curious about her heritage, determined to learn more and make up for many years of disconnection. “I’ve been lucky enough to be involved with global women’s groups and I saw other women taking ownership of their lineage when I’d never really understood mine,” she said. “I’ve always felt a wee bit anchor-less. I’m still cautious about learning more, but now it’s because I don’t want to be seen as an interloper. But I want to be able to be part of, to have that foundation, that anchor.”

Meanwhile, Jillian’s twin daughters, Arielle and Maia (21), have been a huge inspiration in her decision to reclaim her whakapapa, as she sees it as her responsibility to ensure they understand their connection to their Kāi Tahu roots.

“I was always brought up to believe that it’s not about you, it’s about the next generation and their children, and that your job is to make sure they understand their connection to the land, their river, their mountain. That’s how I was always taught to identify who you are.”

Jillian is proud that society has evolved to the extent that Arielle learned te reo Māori in high school – an opportunity that didn’t exist during her own school days – and is now incorporating indigenous studies into her degree at the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

It’s a relief for Jillian to know that her children will not feel the weight of that caution around their culture and identity. “It’s slightly different for Maia, who had a stroke at birth,” says Jillian. “But she is a huge part of the equation of why I want to know about my heritage now, because she has taught me so much about being in the moment, listening to my intuition and my gut.

“Maia's bravery through her brain injury and her everyday learning has shown me her courage with a full and happy heart. The strength she shows allows me to come out from the sidelines and share my voice.”

Thirty odd years later, and Jillian’s intuition takes her back to her childhood and that profound connection to the natural environment. “I still find peace when I’m walking through the bush, seeing the light filter through. All of a sudden different leaves have a different iridescence and the birds come and the leaves crunch and all the senses are filled. That’s what grounds me.”