Reviews The Luminaries

Jul 17, 2014

Nā Eleanor Catton

Publisher Victoria University Press

RRP $55.00

Review nā Aaron Smale

It’s somewhat daunting to try to review a novel that has won the 2013 Man Booker Prize and had great piles of praise already heaped on it from every quarter. What’s left to say?

And where do you start? At over 800 pages just doing a précis is a mammoth injustice to the work itself. But tucked into its massive size is a unique character deserving of closer inspection. He is Te Rau Tauwhare, a character of Ngāi Tahu descent and based on a real person.

In some ways it seems unfair to scrutinise one character in a novel that is teeming with them. It’s almost akin to reviewing one of the violin players in an orchestra who only chips in now and again in a massive symphony. But then if you play violin, you would take more of an interest.

It takes around 100 pages for Te Rau to make a significant appearance. By this stage the reader has already been treated to a wholly formed world that is utterly convincing, with finely wrought details that transport the reader back to the West Coast in the 1860s.

At first the narrator gives a view of Te Rau through the eyes of another character, and this view is fraught with misunderstanding and prejudice. This is conveyed with a light touch, with the author not feeling the need to digress into a kind of an explanation for the tourists. The other character goes to pat Te Rau on the head while he is sitting on the ground and Te Rau flinches. This was a completely convincing reaction for a character who would have held a certain belief in the tapu of the head.

This reaction, although a seemingly minor detail, was the sort of reaction you’d expect from a character who was a Māori man of some standing during 1860s colonial New Zealand. There is no comment on the cultural reasons for this, as this would have been simply drawing attention to something innate to Te Rau and was beyond the comprehension of the character who is looking at him.

However, some of what follows didn’t feel so smooth (for this reader at least) or convincing.

When many of the characters are introduced the narrator will often pause to give a rather dense analysis of the character’s personality before resuming the story. Although this pattern becomes somewhat predictable, the tone of the narrative voice seemed to fit this schema, and suited the characters who were, after-all, Victorian men.

In the overall context of the novel this technique is almost necessary – with that many characters running around there really isn’t the space to dawdle about reflecting on each character’s psychology for any length of time. Particularly in the first half of the book,

it feels like the characters are sketched in. The depth and detail comes later.

The portrayal of Te Rau followed this pattern to some degree. Some of the history of Māori on the West Coast is slipped in without feeling at all intrusive. I did wonder if a man like Te Rau would have thought of himself as Ngāi Tahu or Poutini Ngāi Tahu at that time. Although the land sales of this period would have used those terms, it’s questionable whether it would have been common parlance among South Island Māori themselves. I certainly questioned the term “Ngāi Tahu allegiance” – I think allegiance is something you can give or withhold, whereas whakapapa is simply an inescapable fact.

You could say these details are minor, as we know from our vantage point what is being described. And they are details that would have passed most readers by. But it does raise questions about how accurate a writer of creative works needs to be when it comes to history or a culture other than their own – Shakespeare’s histories are far from accurate, but this certainly doesn’t detract from the writing.

These are external details and something of a soft target. It’s when the writing describes Te Rau’s interior world that things get trickier.

One of the great strengths of the book is the highly ornate Victorian tone of the third-person narrator. This helps hold the book together, with its vivid descriptions of the world of the story and the characters who inhabit it. In many ways this tone suits the characters as they are Victorian men, even though their backgrounds are widely varied.

However, this narrative voice is sometimes overly dominant and in some of the sections about Te Rau it felt awkward at times. You could argue that Te Rau was also a Victorian man, but this doesn’t quite explain it.

In this first encounter the narrator gives a summary of Te Rau’s character and self-image.

In this instance we’re told by the narrator how Te Rau thinks about himself. There was a degree of confusion between the authority of the narrator and the thoughts of the character. The narrative voice seemed to obscure the character rather than revealing him.

This could be attributed to the narrator entering into the head of a character from another culture; however this doesn’t entirely explain it. One of the most enjoyable characters in the book was Ah Sook, who was Chinese. Here I found myself utterly absorbed and convinced by the character.

In another section of the book there is a lovely passage where Te Rau is reflecting on his murdered friend. The shift into his thoughts was seamless, and gave a great insight into Te Rau as a human being.

But then there was a real clanger. While reflecting on where his friend should have been buried Te Rau runs through various options he thinks would have been preferable. One of the options he considers is “beside the plot of his tiny garden.” At that point I reacted with a “Whoa! Hang on a minute!” I thought it highly unlikely that a Māori person would consider burying the dead right beside a source of food. I tried to think of an exception but couldn’t.

My overall impression was that the character of Te Rau was treated with a little too much reverence to the point where it risked him becoming a caricature, almost a Noble Sage if not a Noble Savage. It wasn’t that you wanted him to be a bad guy. It’s just that many of his interactions are quite passive, and it was difficult to get a sense of who he was.

Again, this is a narrow assessment as the book is highly sophisticated in its structure and the way all the characters’ lives are interlocked. Te Rau is but one character in a large orchestra. The symphony still soars.

Aaron Smale was previously the associate editor of Mana magazine and last year won a Canon Media Award for the best magazine feature on social issues.

Aaron Smale was previously the associate editor of Mana magazine and last year won a Canon Media Award for the best magazine feature on social issues.

In 2010 he won the Cathay Pacific Travel Photographer of the Year and completed an MA in Creative Writing at Victoria University in the same year.

Ko te Whenua te Utu – Land is the Price: Essays on Māori History, Land and Politics

Nā M.P.K. Sorrenson

Publisher: Auckland University Press

RRP: $49.99

Review nā Gerry Te Kapa Coates

Professor Keith Sorrenson identifies himself as being of Ngāti Pūkenga and Pākehā descent. This book is a collection of his major writing of the past 56 years, and shows how good he is at explaining the complex ways Māori were colonised. For example, he uses his inside knowledge of the Waitangi Tribunal and his wide experience of African and American colonisation to highlight the parallels between what happened in Aotearoa and other casualties of the British Empire.

Professor Keith Sorrenson identifies himself as being of Ngāti Pūkenga and Pākehā descent. This book is a collection of his major writing of the past 56 years, and shows how good he is at explaining the complex ways Māori were colonised. For example, he uses his inside knowledge of the Waitangi Tribunal and his wide experience of African and American colonisation to highlight the parallels between what happened in Aotearoa and other casualties of the British Empire.

He says, “For me there was always the puzzle of why Native Americans got some 370 treaties, which were largely ignored during the European occupation of their continent…. whereas New Zealand’s single Treaty of Waitangi had been forever present, if not always observed.” Many of the words in these treaties are very similar to those used in the Treaty of Waitangi, and, he says, “…the three articles of the Treaty are deeply embedded in an older colonial policy, drawn from the various corners of the empire.” Busby of course knew about these American precedents, so it is not surprising that he made use of them in our Treaty, which Sorrenson calls “our enduring struggle.” His essays look at various aspects of how the British viewed New Zealand and the Māori, and how those views and attitudes changed over time, from assimilation to representation.

The alienation of land through the actions of settlers like lawyer F.D. Fenton are recounted in the essay “Folkland to Bookland”. Sorrenson points out the analogies between what happened under the English enclosure movement that “completed the long transition from communal to individual property” in Britain, and what Fenton, who became the first chief judge of the Native Land Court, managed to achieve in New Zealand.

The decision not to update the essays for this publication is at times disconcerting, because they remain stuck in time. Treaty settlements now finalised may not have been at the time the essay was written. That aside, Sorrenson writes in a style which can enthral anyone with an interest in the big picture of why Māori are where we are, how it happened, and how it might play out in the future. This is a very thoughtful and worthwhile book.

Gerry Te Kapa Coates (Ngāi Tahu) is a Wellington consultant and writer.

Gerry Te Kapa Coates (Ngāi Tahu) is a Wellington consultant and writer.

Maranga Mai!

Te Reo and Marae in Crisis?

Editor: Merata Kawharu

Publisher: Auckland University Press

RRP $45.00

Review nā Aaron Smale

Recently I was eavesdropping on a conversation between my eldest aunty and a younger man who is related to us by marriage. Both are fluent in te reo. Among other things they were discussing the merits of the taumata of a particular marae and the individual who is the principal speaker. My aunty made allowances for this man because the senior kaumātua of the marae is in ill-health. But our whanaunga member was having none of it – he was appalled at the decline in abilities and mana that he believed this individual represented.

Recently I was eavesdropping on a conversation between my eldest aunty and a younger man who is related to us by marriage. Both are fluent in te reo. Among other things they were discussing the merits of the taumata of a particular marae and the individual who is the principal speaker. My aunty made allowances for this man because the senior kaumātua of the marae is in ill-health. But our whanaunga member was having none of it – he was appalled at the decline in abilities and mana that he believed this individual represented.

In many ways this book is about this very debate: how are marae coping with the changes happening in Māori society, and are they fulfilling their purpose of being a bastion of Māori language and tikanga?

The included essays are eclectic in the range of voices and topics they cover, from the deep reminiscences of kuia Merimeri Penfold approaching her 100th year, to academics from a range of disciplines. Each throws interesting light on a complex subject, and the book will engage different people on different levels for that reason. The essay by anthropologist Paul Tapsell, which gives an overview of the history of how marae have developed from their Pacific origins through to the present day, is quite amazing for the territory it covers in such a short space.

Although the book is focused on Tai Tokerau, the issues are common to Māori communities throughout the country, and anyone with a passing interest in their marae will recognise their own situation in these pages.

The picture the book paints is fairly ominous, with occasional flickers of hope. All of the essays note the devastating effects of urban drift on the fabric of once-thriving communities that had marae as a focal point. While the numbers of kaumātua and kuia are dwindling fast, those who should be stepping into their roles simply aren’t there because economic imperatives have taken them to other parts of the country, or even further afield.

While the essays touch on the underlying economic reasons for these issues, many are addressing it on a purely cultural level. There is mention of economic renewal in some communities on the back of fibre-optic and mānuka honey businesses. Treaty settlements have helped and will help many iwi in developing an economic base. But the book’s length and scope doesn’t allow it to delve into these issues in any depth.

In the long-term, reviving the language and the cultural sustenance of marae communities can only happen if there is an economic basis to that community. After all, it was often the resources of a location that gave rise to a pā or marae emerging there in the first place.

Aaron Smale was previously the associate editor of Mana magazine.

Aaron Smale was previously the associate editor of Mana magazine.

He lives in Levin and is of Pākehā and Ngāti Porou whakapapa.

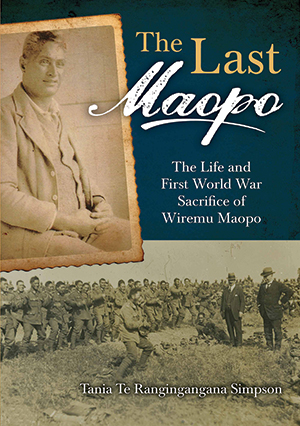

The Last Maopo – The Life and First World War Sacrifice of Wiremu Maopo

Nā Tania Te Rangingangana Simpson

Publisher: Oratia Media

RRP: $34.99

Review nā Tā Mark Solomon

The Last Maopo is the story of Wiremu Maopo, who joined the second Māori Contingent to fight in World War I, told mainly from his letters to his friend Virgie. It is also the story of the author’s journey of discovery of her tūpuna.

The Last Maopo is the story of Wiremu Maopo, who joined the second Māori Contingent to fight in World War I, told mainly from his letters to his friend Virgie. It is also the story of the author’s journey of discovery of her tūpuna.

Tania Simpson (Ngāi Tahu, Tainui, Ngāpuhi) is the great-granddaughter of Wiremu Maopo, from a line he didn’t know existed. He came from a large family, one of 13 children born to Te Maiharanui Maopo and Ani Wira of Taumutu. The family

was decimated by disease and by the time he left for the war, only his father and a sister had survived. When he returned, he was the only one left. He didn’t know that his girlfriend Phoebe had given birth to a daughter who would carry on his line.

It is an awesome book and I loved it.

I could certainly understand the passion of the author striving to understand her family history, and I was in awe of the letters of Wiremu Maopo, who was obviously a real gentleman.

One thing that stands out was the closeness between him and the Pākehā community. And his letters are dignified – there is little indication of the bitterness and horror of the war until his third year over there when some despair at the conditions starts to creep in. But he doesn’t shy away from the realities. In one letter he tells the story of returning from a mission when a shell lands next to him and his mate. When it explodes, he and his mate are showered in mud while four British soldiers and a horse right next to them are killed. Another time he writes of watching a soldier literally being blown apart by a shell.

It is also an incredibly sad story about Wiremu and his family and the fact that he went to his grave thinking he was the last of his line. It is a fascinating read on so many levels, I would recommend it to anyone.

Tā Mark Solomon is Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Kaiwhakahaere.

Tā Mark Solomon is Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Kaiwhakahaere.