Reviews

Dec 20, 2020

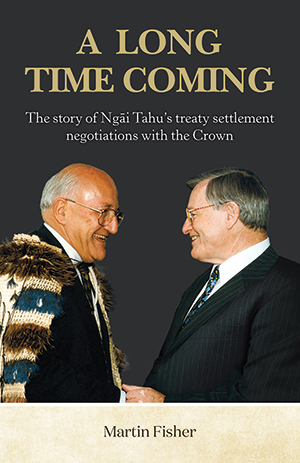

A Long Time Coming: The story of Ngāi Tahu’s treaty settlement negotiations with the Crown

Nā Martin Fisher

Canterbury University Press

RRP: $39.99

Review nā Michael Stevens

A Long Time Coming is an important and judicious book. As the full title indicates, it covers the period, processes and personalities involved between the Waitangi Tribunal releasing the Ngāi Tahu Land Report in 1991 and Parliament passing the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement 1998.

A Long Time Coming is an important and judicious book. As the full title indicates, it covers the period, processes and personalities involved between the Waitangi Tribunal releasing the Ngāi Tahu Land Report in 1991 and Parliament passing the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement 1998.

In retrospect, because we know a settlement package was negotiated and given effect to, and we know Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu was established as part of this, these events appear inevitable, perhaps even orderly. In eleven short chapters, historian Martin Fisher shows that to be anything but true. Instead, as he notes at p.129, “it was a minor miracle that an agreement was signed when it was.”

This book begins with a brief overview of Ngāi Tahu whakapapa, history, mahinga kai traditions, entanglement with the British imperial world, the colonisation of Te Waipounamu, and the development of Te Kerēme, the Ngāi Tahu Claim. The next chapter outlines Ngāi Tahu engagement with the modern Treaty of Waitangi claims process that developed from the mid-1970s. The following eight chapters focus on events between 1991 and 1998. The final chapter and a short Afterword sketch out post-settlement Ngāi Tahu successes and failures before concluding with two pertinent observations: that the South Island’s majority culture can no longer ignore Ngāi Tahu as it once did, and that the Ngāi Tahu settlement, though imperfect, “as a process of reconciliation … changed New Zealand forever.”

Drawing upon a range of primary source evidence, especially records held by the Office of Treaty Settlements and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, Martin illustrates the many variables and contingencies at play, and the huge ebbs and flows in negotiations. This rich material is skilfully interwoven with interviews Martin conducted with key Crown agents and Ngāi Tahu representatives, as well as a wide body of secondary literature. The upshot is a detailed picture of the enormous difficulties faced by both Ngāi Tahu and Crown negotiators.

A particular difficulty was the way in which third party entities such as the Royal Forest and Bird Society worked hard to successfully scuttle or dilute opportunities for Ngāi Tahu to acquire state-owned lands the government wished to dispose of. Forest and Bird likewise exerted considerable pressure to limit Ngāi Tahu involvement in and on the conservation estate, which constitutes so much of Te Waipounamu. Ostensibly motivated by the modern religion of preservationist conservation, Forest and Bird’s views and tactics, and those of kindred groups, reveal them to be, at root, as antagonistic towards Māori as the most intolerant nineteenth century Christian missionaries. The book’s more important point though, is the huge power imbalance at the heart of negotiations, and the way in which the Crown was simultaneously defendant, Judge and jury. In such a challenging environment, Ngāi Tahu needed, but fortunately had, an astute leadership team. By any reading, A Long Time Coming is an affirmation of the high levels of trust that Ngāi Tahu whānui placed in its negotiators.

Another of the book’s key themes is the central importance of New Zealand’s 35th Prime Minister, James Bolger, and his relationship with Tā Tipene. This was especially critical after initial negotiations with Sir Douglas Graham (as Minister of Treaty Negotiations), which began 1991, broke down in late 1994. In response, Ngāi Tahu commenced aggressive legal proceedings throughout 1995. In the midst of this acrimony, it was Bolger who brought Ngāi Tahu back to the negotiating table in early 1996. And it was Bolger who kept negotiations on track to arrive at a Heads of Agreement in October 1996, and a Deed of Settlement in November 1997, that sufficiently “enhanced the mana of Ngāi Tahu and restored the honour of the Crown.” The two biggest internal government critics of the treaty claims process, for Ngāi Tahu at least, were Treasury and the Department of Conservation (DoC). This was not just evident to Ngāi Tahu. In 1997 a high-ranking official from the Office of Treaty Settlements described DoC’s criticism towards Ngāi Tahu and its settlement as “as much attitudinal as process.” Bolger, it seems, broke through many of DoC’s and Treasury’s roadblocks at important junctures. At the same time, he made fiscal constraints and political bottom lines abundantly clear to Tā Tipene and the wider Ngāi Tahu negotiating team. On Bolger’s watch, everyone swallowed proverbial dead rats to achieve, under the circumstances, a reasonable outcome. Unsurprisingly then, it is an image of Bolger and Tipene that graces the book’s cover.

However, Martin Fisher is no born-again Thomas Carlyle. This is more than a history of Great Men. He acknowledges, for example, “the hundreds if not thousands, of people who provided helping hands, whether in the boardroom, the archives, the wharekai, on the road and at sea to arrive at the Ngāi Tahu settlement” whilst noting their names are not represented in the negotiations themselves. A Long Time Coming also outlines the critical positions taken by two Ngāi Tahu wāhine and members of Parliament – Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan and Sandra Lee – and respectfully details their concerns with settlement negotiations and the eventual settlement.

I am repeatedly told that one should forgive one’s enemies, but write down their names. To some extent, Martin Fisher has done that important job for Ngāi Tahu with respect to the 1990s period. Just as importantly, he has also recorded the names and deeds of several of our allies. In doing all of these things, Martin is something of a latter-day Harry Evison: a top-notch historian, a Pākehā New Zealander committed to social justice, and a friend of Ngāi Tahu. We are lucky indeed to have him on staff at the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, for which credit must go to its Director and Upoko o Ngāi Tūāhuriri, Dr Te Maire Tau.

A Long Time Coming is a small, perhaps even understated book, but it rests on rigorous scholarly research and analysis. As Tā Tipene O’Regan rightly notes in its Foreword, “this work will stand as the definitive account of a significant phase in this nation’s historical journey.” However, the text is simple and its arguments concise. This book is therefore accessible to a wide readership. In other words, not only should rank and file Ngāi Tahu – indeed, all New Zealanders – read this book, they are easily able to do so. That in itself is a considerable achievement for which Martin Fisher should be thanked and praised. Placing a copy of this book in every Ngāi Tahu whānau would make us a wiser and better people. Placing a copy in every New Zealand library and school would make this a wiser and better nation.

Michael Stevens is the Alternate Representative to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu for Te Rūnaka o Awarua. An independent historian, he is currently co-editing volume 2 of Tāngata Ngāi Tahu and completing a book on Bluff as the 2020 Judith Binney Fellow.

Michael Stevens is the Alternate Representative to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu for Te Rūnaka o Awarua. An independent historian, he is currently co-editing volume 2 of Tāngata Ngāi Tahu and completing a book on Bluff as the 2020 Judith Binney Fellow.

Te Hāhi Mihinare

The Māori Anglican Church

Nā Hirini Kaa

Bridget Williams Books

RRP: $49.99

Review nā Tui Cadigan RSM

As a Katorika Māori I accepted an invitation to review this book although I was wondering if I was the appropriate person to undertake this work. Once I started, it gripped my mind, heart and spirit as I was drawn into a thorough exploration of the meeting between Māori and Te Hāhi Mihinare.

As a Katorika Māori I accepted an invitation to review this book although I was wondering if I was the appropriate person to undertake this work. Once I started, it gripped my mind, heart and spirit as I was drawn into a thorough exploration of the meeting between Māori and Te Hāhi Mihinare.

This is an historic account that encompasses not only the history of this Hāhi but shows much of the impact of colonisation on iwi and the practical engagement of missionaries with Māori from their first encounters and the reality of the racism of that time. The reader is taken on a wonderfully articulated chronological journey beginning from 1814 written as a history yet I think a deeply personal telling of a faith journey too.

The tensions between traditional spiritual knowledge and the missionary understanding of cultural uniqueness of Māori, existing religious practices, language differences and interpretation made the journey complex indeed. What the reader is treated to in this book is a walk through the whakapapa of the brilliant minds of Māori leadership that I fear is missing today. Outstanding figures such as Apirana Ngata, Frederick Bennett, Pine Tamahori, Hoani Parata, James Henare and generations of the authors own Kaa whānau to name but a few, from a range of iwi and Hāhi who engaged with the dynamics of faith, politics, religion and societal whanaungatanga over decades. These orators left legacies that are still recalled and sited as points of reference in discussions to this day.

This work incorporates the formation and influence of significant groups such as Te Rūnanga Whakawhanuaunga i Ngā Hāhi and the Māori Women’s Welfare League in relation to Te Hāhi Mihinare and examples of the tensions that existed with the Missionary Society and the ongoing struggle for Māori autonomy within the Hāhi. The development of ecumenism, the influences of Liberation Theology and the Feminist Movement and the exertion of control by the Pākehā hierarchy makes for an enriching read from multiple perspectives. The author has produced an honest telling of the history of Te Hāhi Mihinare with real integrity.

Having studied at Te Rau Kahikatea in the late 1990s and after reading this book I wish it had been available as a resource at that time. The author notes the timidity of some Māori to say what they really meant for fear of upsetting the Pākehā Church hierarchy, which is understandable in the times but none the less sad. I would just add that this book should be compulsory reading for all studying for ministry in Aotearoa regardless of Hāhi or iwi, ethnicity or gender. It has much to teach those who read with an open mind and listening heart.

Tui H L Cadigan affiliates to Kāi Tahu Iwi and Kāti Māhaki ki Makaawhio hapū. She is Kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Te Hāhi Katorika o Aotearoa and a member of Ngā Whaea Atawhai o Aotearoa.

Tui H L Cadigan affiliates to Kāi Tahu Iwi and Kāti Māhaki ki Makaawhio hapū. She is Kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Te Hāhi Katorika o Aotearoa and a member of Ngā Whaea Atawhai o Aotearoa.

Opinions expressed in REVIEWS are those of the writers and are not necessarily endorsed by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.