ReviewsBooks

Dec 21, 2014

SPOONBILL 101

Nā Rangi Faith

Puriri Press 2014

RRP: $25.00

Review nā Gerry Te Kapa Coates

Review nā Gerry Te Kapa Coates

This is a purist’s book of 60 eclectic poems where the writer is accessible only through his work – no cover blurb, photo, or notes on the poems. I admit I cheated and checked his website: www.rangifaith.co.nz. Faith is a Kāi Tahu Māori and Moriori and the poems certainly reflect his interests in the outdoors and in Māori issues (such as Māori Land Court hearings), as well as art and culture, archaeology, and history in general.

The poems are almost all just a single page. The title poem, Spoonbill 101, is a whimsical look at how the kōtuku got its bill. “When the lagoon birds/ were lined up/ for panel beating/ & noses and names handed out–/ this kōtuku’s beak/ was hammered flat–.” Hence “kōtuku ngutu papa”. Some poems are evocative, yet the meaning remains elusive – for example, “When the sailing ends”, about “that midnight race/ to the hospital” and a girl who “would walk home/ in the dark with her sister/ holding hands.”

War features in several poems: P.O.W., The Last Tree, and Home Guard at the Pancake Rocks. In A Poppy for our fathers, about the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, the poet says, “Let the poppy fall/ from your fingers/ into the Arno–/ it will drift under that bridge/ spared destruction/ in a world war” – again evocative, but still ultimately mysterious. Writers like Hone Tuwhare and Janet Frame make cameo appearances.

The outdoors and the West Coast and its coal are subjects too – from .303s to a truck with “sodden dogs on the back,/ ears flattened with cold.” Also featured is Brunner, the English surveyor/explorer reflecting on his dog Rover (and by saying “though Kehu was my staff”, belatedly acknowledging his life-saving Māori guide). There is even a poem about the destruction wrought by the Rena’s sinking in the Bay of Plenty, told through colours: “Pango–/ birds in Number 6 bunker oil/dripping from beaks,/ a fin rising offshore” and “whero–/ red is the colour/ of angry people.”

These are all very diverse and personal poems that stand to be read several times and mulled over to soak up their flavour. Faith is a prolific poet and has been widely published in a number of unlikely tabloids. May he continue to write many more. Kia kaha, kia tū e hoa whanaunga.

Gerry Te Kapa Coates (Ngāi Tahu) is a Wellington consultant and writer.

Gerry Te Kapa Coates (Ngāi Tahu) is a Wellington consultant and writer.

The Value of the Māori Language – Te Hua o Te Reo Māori, Volume Two

Edited by Rawinia Higgins, Poia Rewi and Vincent Olsen-Reeder

Huia Publishers

RRP: $45.00

Review nā Lynne Harata Te Aika

Review nā Lynne Harata Te Aika

Me mihi ka tika, ki a Pokotaringa, Ngākaunui, Whakaihi! This is a collection of essays, written in te reo Māori and English by passionate, committed, and staunch Māori language activists spanning three or more generations. There are 30 contributors including revered language pioneers Timoti Karetu, Wharehuia Milroy and Iritana Tāwhiwhirangi, active in the Māori language movement since the 1960s and still going strong. The next generation, mainly university graduates from the 1980s–90s, are now maturing in age and are grounded in experience – not just talking te reo talk, but walking the language journey in their respective fields. They come from a range of backgrounds including television, radio broadcasting, education, parliament, iwi, wānanga and universities, and law. Their narratives include historical documentation of language revitalisation initiatives, commentaries on language developments, and healthy critique of government and institutional policy and practice. Our own Hana O’Regan reflects on the Ngāi Tahu tribal revitalisation programme Kotahi Mano Kāika. We are forewarned about keeping our youth generation engaged in language learning and maximising technology to achieve this.

The value of the Māori language since the 1987 Māori Language Act is analysed, debated, deciphered, and decreed in many different forms. The youngest generation of language masters, the likes of Paraone Gloyne and Korohere Ngāpō, graduates of Te Panekiretanga o te Reo and protégées of the language pioneers, show that the intergenerational transfer of language activism is in a healthy state. Ko tōku reo, tōku ohooho, tōku māpihi maurea, tōku whakakai marihi!

Lynne Harata Te Aika (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Awa) is the Head of Aotahi School of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Canterbury. She is involved in Ngāi Tahu education, te reo and cultural initiatives at a rūnanga, hapū, and tribal level.

Lynne Harata Te Aika (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Awa) is the Head of Aotahi School of Māori and Indigenous Studies at the University of Canterbury. She is involved in Ngāi Tahu education, te reo and cultural initiatives at a rūnanga, hapū, and tribal level.

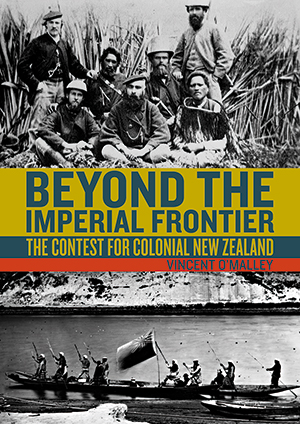

Beyond the Imperial Frontier – The Contest for Colonial New Zealand

Nā Vincent O’Malley

Bridget Williams Books

RRP: $49.99

Review nā Martin Fisher

Review nā Martin Fisher

This is an excellent collection of essays that challenges our conceptions of the frontier in New Zealand. O’Malley has been involved in the Treaty claims process as a historian through both the Crown Forestry Rental Trust and the Waitangi Tribunal for over 20 years, and the breadth and depth of his writings are evidence of his longevity. The frontier topics covered include pre-Treaty encounters between Māori and newcomers; the scope, intent, and nature of post-Treaty deeds of purchase; analyses of interactions between Māori and English laws and mechanisms of governance; the role of confiscation and war in the Waikato and the East Coast; capital punishment; and the Native Land Court. Each chapter tests the notion of a rigid frontier, and instead depicts a fluid and ever-changing boundary between the worlds of Māori and the newcomers who settled here.

Perhaps the most illuminating chapter is Beyond Waitangi: Post-1840 Agreements between Māori and the Crown, in which O’Malley makes a compelling case for re-thinking the nature of some of the major land purchases that came after the Treaty of Waitangi, including the Ngāi Tahu purchases (1844–1864). O’Malley compares the situation to the numbered Treaties that were negotiated in Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These Canadian treaties mirrored the land purchases of the pre-Native Land Court era in New Zealand, but were also intended to establish a concrete relationship between indigenous groups and the Canadian government. O’Malley argues and provides evidence to show that the small payment often made in early Crown purchases of Māori land (1840–1865) and the minimal reserves that were provided were only a minor part of the agreement. Crown promises of schools, hospitals, and the benefits of having settler communities nearby were portrayed as the far more valuable and long-term benefit, and would have persuaded rangatira Māori across the country to sign the agreements.

O’Malley’s referencing is on the whole excellent, but with such an abundance of sources it would have been far more useful to have footnotes rather than endnotes, as the reader continually needs to flip back and forth. In addition, the two essays on Māori and English laws and mechanisms of governance repeated information (at times nearly verbatim), and could have been combined into one chapter. Other than those minor issues, this collection stands out as an important contribution to our understanding of the history of the frontier in New Zealand, and how that history continues to resonate in the politics of the present.

Martin Fisher was born in Budapest, Hungary but was raised in Canada and New Zealand. He is a lecturer at the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre at the University of Canterbury.

Martin Fisher was born in Budapest, Hungary but was raised in Canada and New Zealand. He is a lecturer at the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre at the University of Canterbury.

First Readers in Māori (reo Māori)

Huia Publishers

RRP: $40

Review nā Fern Whitau

Review nā Fern Whitau

First Readers in Māori is a set of 10 little pukapuka designed to assist us on our Māori language journey. Each book is in te reo Māori with a glossary that provides an English translation.

Reading these stories will help with learning the reo Māori words for numbers, colours, shapes and the names of some animals and toys. They will help when having conversations about the child’s world with words like see-sawing, swinging and sliding; pīoioi, tārere, reti. The reader will learn how to ask for things and descriptive words like big, small, long, and heavy; nui, iti, roa, taumaha.The illustrations in these pukapuka are fun and bright and the subjects delightful. This is a great resource for children and adults learning te reo Māori and of course for story time. But to me the main appeal is the vocabulary, which will be very useful when interacting with our tamariki and mokopuna, especially for parents or grandparents who are bringing their children up to be bilingual.

Fern Whitau (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha) is a te reo Māori advisor at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Moeraki is her tūrakawaewae and she is a proud tāua who loves to read to her mokopuna.

Fern Whitau (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha) is a te reo Māori advisor at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Moeraki is her tūrakawaewae and she is a proud tāua who loves to read to her mokopuna.