Tangata WhenuaAn Illustrated History

Dec 21, 2014

It charts the sweep of Māori history from ancient origins through to the twenty-first century and it has been called one of the most significant books on the Māori world ever written.

It charts the sweep of Māori history from ancient origins through to the twenty-first century and it has been called one of the most significant books on the Māori world ever written.

Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History by Atholl Anderson, Judith Binney and Aroha Harris is an ambitious book from Bridget Williams Books, 544 pages and 500 images covering Māori history from ancient origins through to the 21st century.

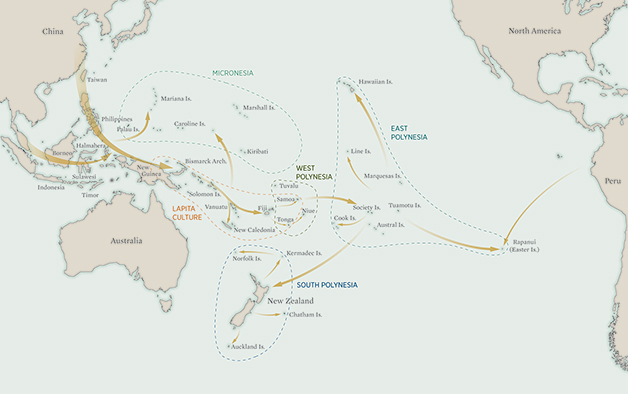

The story begins with the migration of ancestral peoples out of South China, some 5,000 years ago. These early voyagers arrived in Aotearoa early in the second millennium AD, establishing themselves as tangata whenua in the place that would become New Zealand Today, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Māori are drawing on both international connections and their ancestral place in Aotearoa.

Ngāi Tahu have played a leading role in Tangata Whenua. Atholl Anderson wrote the chapters about the early origins of Māori, Kāi Tahu historian Michael Stevens is a contributor and researcher, Tā Tipene launched the book and the Ngāi Tahu Fund supported the book financially.

We bring you an excerpt from one of the early chapters written by Atholl Anderson.

The origins of Māori and Moriori

The ancestors of Polynesians came almost entirely from Holocene age Southeast Asian populations. They spoke languages of the Malayo-Polynesian family, the most widespread of the Austronesian languages, and they had developed an unusual competency in seafaring based on the sailing canoe. During migration eastward there was some intermarriage with Melanesian men, themselves descended from much earlier inhabitants of Southeast Asia, especially in the offshore islands of New Guinea. Societies at that time were matrilineal and matrilocal. The crucial movement for Pacific settlement was by people of the Lapita culture, from the Bismarck Islands, who began a rapid dispersal into previously unoccupied islands in the Central Pacific between 1100 and 800 BC, reaching as far eastward as Tonga and Samoa. In these latter groups, probably within the first millennium AD, a distinctive Polynesian culture developed; and around the end of the first millennium AD, migrants from West Polynesia reached the central islands of East Polynesia. Here, under different conditions of social mobility, cognatic descent and patrilocality prevailed. Later, colonisation expanded north, east and south-west into the other unoccupied islands of East and South Polynesia. It is possible that there was a small component of South American migration into East Polynesia.

Carved whaletooth pendant (mau kakī) from the Nelson region, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, ME001545 (page 38).

The capability of Polynesian voyaging remains a contentious issue. One hypothesis favours an ability to sail to windward that would have made even long passages relatively easy and rapid. Another argues that windward sailing did not arrive in East Polynesia until after the early migrations, which, consequently, must have been difficult and possibly reliant upon contingencies of climatic change that produced windows of favourable sailing conditions.

However they travelled, it is apparent that South Polynesian colonists came from the Tahitic-speaking region of the Society, Cook and Austral island groups, arriving as a substantial migrant population. A longstanding debate about when South Polynesia was first colonised has now been

resolved in favour of a period beginning about the mid-thirteenth century.

Whalebone lizardshaped amulet, Wainui on the East Coast, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, ME000643 (page 30).

People reached New Zealand first, probably because of its relatively immense size, but soon afterward explored the surrounding seas, finding and settling briefly in the Kermadecs, Norfolk Island and the Auckland Islands. A group of the early migrants, probably after reaching New Zealand, also found and settled the Chatham Islands, where they remained as a permanent population of Moriori. Māori and Moriori were the tangata whenua who challenged the arrival of Europeans.

Speaking of Migration, AD 1150–1450

All Māori and Moriori knowledge about the past was handed down over the generations in the form of oral traditions attached to genealogies, or whakapapa. The content of traditions was open to debate among groups but it was not doubted as containing fundamental historical evidence, and tribal traditions continue to be taken today as the stuff of history on every marae in the land – that is, as a sequential record of actual people and events. Yet in the broader fields of historical and anthropological scholarship, and widely in popular discussion, the historical credentials of tribal traditions have often been debated, scorned or ignored. The historical reliability of traditions and their perspectives on migration are the subject of this chapter.

Tauihu, Te Toki-a-Tāpiri, one of the last of the famous waka taua of the early nineteenth century, Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, 150 (page 24).

History mattered for Māori and Moriori, both philosophically as a duty toward the ancestors and pragmatically as a means of contemporary advantage in gaining and holding status and property. In both respects it needed to be reliable, and reliability followed a principle readily predictable in the oral traditions of a chiefly society: it correlated positively with status. Matters of high status, such as circumstances of initial colonisation, direct lines of chiefly descent from founding canoe ancestors, important transactions of marriage and alliance, and the fortunes of war, were essential societal records underpinning relations within and among groups. No less than other kinds of historical records, but perhaps no more so, traditions were also partial, sometimes contradictory, and open to manipulation. Even so, an overall consistency of whakapapa, coupled with intricate, deep and widespread lineage connections, substantiates the claim of traditions to historical intent and comparative reliability. Once conceded, that point has important implications for considering migration traditions. This chapter argues that the concept of a fleet, or fleets, of migration canoes is no Pākehā invention; that it is sustained by whakapapa reaching back to canoe ancestors; and that an historical Hawaiki was distinguished clearly from mythological concepts.

For early European travellers, history worth the telling was not expected in the South Seas (the popular name of the time) and least of all in New Zealand. Johann Forster, naturalist and antiquarian on the Resolution, 1772–75, thought that history was ‘not quite neglected’ by Tahitians, but that, in the absence of writing and a means of recording time, only ‘rude annals’ of it had been preserved in poetry and song. As Tahitians were seen by eighteenth-century Europeans to stand at the apex of East Polynesian cultural accomplishment, no record of ancient history was anticipated in New Zealand; there, as Forster argued, ‘removal from the tropics towards the colder extremities of the globe, together with the gradual loss of the principles of education greatly contribute to the degeneracy and debasement of a nation into a low and forlorn condition’. Not surprisingly, little history was heard or discussed by Europeans. In 1769, Tupaia, the Raiatean interpreter on the Endeavour, spoke at length with Māori at Tolaga Bay about their traditions and his, and later noted a remark by Topa, a chief in Queen Charlotte Sound, about Māori origins in Hawaiki. However, Tupaia was dismissive of local knowledge in speaking with James Cook and Joseph Banks, so not much of what he heard was recorded. Early European attention focused instead upon religious ideas about a pervasive ‘Atua’ (a divinity who could act benignly or maliciously), the departure of spirits at Rēinga, and the doings of Maui. In the early nineteenth century, the most ancient Māori origins were sought through the comparative study of language and myth, and sometimes claimed as found in biblical stories. For missionaries especially, that served only to demonstrate the extent of subsequent cultural degeneration by Māori.

Tauihu, Te Toki-a-Tāpiri, one of the last of the famous waka taua of the early nineteenth century, Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, 150 (page 24).

WIN

TE KARAKA has two copies of Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History to give away. To enter the draw, send your name and address on the back of an envelope to The Editor, TE KARAKA, PO Box 13 046, Christchurch 8141 and mention that you would like a copy of Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History, or email [email protected] with Tangata Whenua in the subject line. We will contact the winners and announce them in the following issue.