The Blue Book

Aug 4, 2025

Tucked away in filing cabinets, whānau bookshelves and tribal archives, the Blue Book is an unassuming yet enduring symbol of Kāi Tahu identity – part whakapapa record, part legal document. For many it’s more than a ledger, it’s a taonga, linking past and present, and a reflection of the long and complex processes that have shaped our iwi. Kaituhi ANNA BRANKIN reports.

ORIGINALLY CREATED TO DETERMINE WHO WOULD BENEFIT FROM THE Crown’s eventual settlement with Ngāi Tahu, the Blue Book was born out of necessity. “It’s a fascinating document and an interesting premise to remind ourselves that it was derived as a systematic list of people through whom you could claim a right to benefit from iwi funds,” says

Tā Tipene O’Regan.

“We actually date the Ngāi Tahu claim to 1848, when Kemp’s Deed was signed, transferring much of Canterbury to the New Zealand Company,” he says. “It was the following year that Matiaha Tiramōrehu wrote to the Crown stating that we wanted those contractual relationships to be honoured.”

Although vast areas of Te Waipounamu had been sold to the Crown – usually for a nominal sum – the Crown had failed to fulfil promises to set aside adequate reserves for our people to live on, and to build schools and hospitals. Within a generation Ngāi Tahu had lost most of its land and resources. What followed were decades of petitions, hearings and official inquiries – most of which recognised the wrongdoing, but failed to deliver redress.

Finally, the 1921 Native Land Claims Commission ruled in favour of Ngāi Tahu and recommended a payment of £354,000. “Even then, there continued to be a deathly silence from the government of the day,” says Joseph Hullen, Senior Whakapapa Adviser at Te Rūnanga o

Ngāi Tahu. “They couldn’t ignore our claim altogether, thanks to the work of advocates like H.K. Taiaroa and others, but they could ignore or make difficult its recommendations.”

Joseph Hullen

Eventually, a list of beneficiaries was required – and whakapapa became the basis on which people would qualify. The work of compiling that list began in 1925, when the Native Land Court established the Ngāitahu Census Committee to help identify who was eligible, using records from Crown censuses in 1848 and 1853.

But inclusion wasn’t straightforward. Two potential approaches quickly emerged – the Taiaroa Committee argued that anyone who could prove Kāi Tahu ancestry should be eligible, while the Pitama Committee stated that only those who descended from kaumātua living within the boundaries of the Kemp’s Deed area should be included.

The differing perspectives resulted in extensive deliberations, and ultimately the Native Land Court convened a hearing at Tuahiwi, finding in favour of the Taiaroa Committee’s approach.

Joseph sees both sides, but he thinks the right decision was made in the end. “There are people that say the claim was based on Kemp’s Deed and therefore it should have been only those kaumātua who were living in the rohe when it was sold in 1848 – I get that,” he says. “Others

recognised that this was just the first part of our grievance process against the Crown, and that it therefore made sense to include all the names.”

Once that matter was settled, a two-month wānaka followed, compiling a list of beneficiaries based on whakapapa. Whānau kōrero was shared; files were studied at the Māori Land Court; applications were vetted.

The second Ngāi Tahu Census Committee, convened in 1929, reviewed the list further. They sat at Kaiapoi, Temuka, Dunedin and Invercargill, recommending additional names for inclusion. And while some names were lost along the way, the final list was, as Tā Tipene put it, “just about as good as we were going to get.”

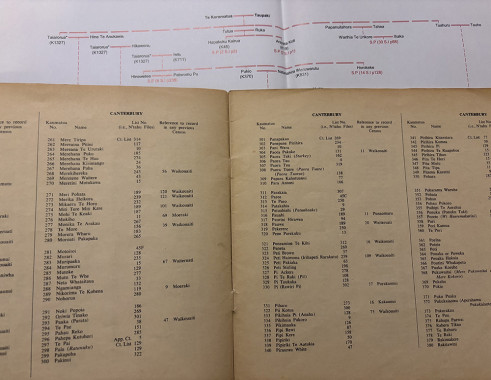

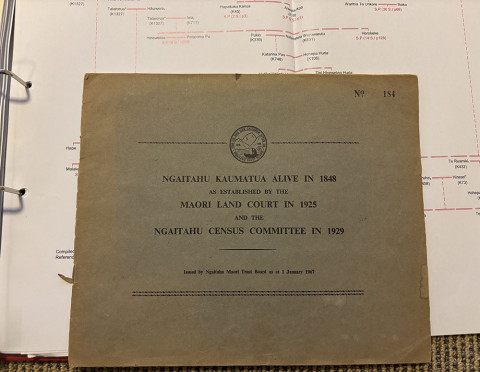

The first published version of this work was released in 1963. Known as the Pink Book, it included names from the 1925 Land Court hearings only. But following amendments to the Māori Purposes Act in 1966, the list was updated to include names gathered by the 1929 Census Committee. That updated list – printed in blue – became known as the Blue Book, in keeping with its predecessor’s nickname.

"It is important, though, that we should pay tribute to the efforts of Frank Winter in bringing the creation of the Blue Book to fruition,” Tā Tipene says. “When he died in 1976, he left us a legacy which he had been involved in creating for nearly his whole adult life.”

In his role as a clerk serving Judge Gilfedder on the Ngāitahu Census Committee in the 1920s and 1930s, the young Frank Winter was very aware of the document’s significance, and when he became chair of the Ngāitahu Trust Board later in life he spearheaded the movement to see the list published. “He had an unrivalled grasp of the challenges, as well as the strengths, weaknesses and omissions of the Pink Book. Officially titled Ngaitahu Kaumatua Alive in 1848 as Established by the Maori Land Court in 1925 and the Ngaitahu Census Committee in 1929, the Blue Book could be bought for five shillings. For many whānau it was the first tangible record that connected them to their iwi.

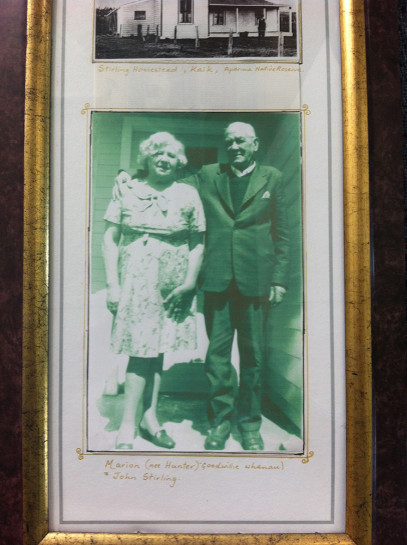

For Muriel Johnstone it has long been a treasure and a teacher. Her first encounters were in her grandparents’ whare in Riverton. “Times spent with my maternal grandparents Gagi and Taua-Nana (John and Marion Stirling) led to my being acquainted with the Pink and Blue books – pukapuka taonga carefully brought out from a little old case in the top drawer of the bedroom dresser where they were kept alongside handwritten manuscripts.”

Muriel Johnstone

Muriel's parents

On one visit young Muriel sneaked a peek at the books. “I became so engrossed lying on the floor reading page after page, when I heard my taua’s footsteps coming up the passage,” she says. “Instead of the good scolding I expected she said, ‘Well dear, if you really want to read all those pukapuka and understand who and what you’re looking for, you best get up on this bed with me and I’ll show you how to do it.’ ”

On another occasion Muriel asked her grandfather to show her the books before he put them away. “Pōua sat me down and opened up the Pink Book first, explaining that it abounded with the many names that helped prove how and who our iwi is, our collective whakapapa,” she

says. “Then he showed me the Blue Book, set out very differently listing Ngāi Tahu kaumātua and where they come from, based on the census of 1848 and 1853. ‘Mind you,’ he said, ‘some were probably absent, at nohoanga, travelling or chose not to take part!’ ”

That memory remains precious, but it also sharpens Muriel’s understanding of the Blue Book’s limitations – the potential for names to have been missed out. It’s a shortcoming that Tā Tipene says is well understood, reflected by the fact that if whānau are able to provide evidence, they can petition to have their tīpuna included.

“There may still be people who will be able to find their way back onto our lists, who are not currently in the Blue Book,” he says.

“However, you can say this for it – practically no other tribe has a Blue Book equivalent, and it has been an integral part of the work of our Whakapapa Unit. Their biggest challenge is piecing together those bits of missing information.”

Joseph agrees, saying: “I love the fact that we’ve got it, but it’s equally frustrating because there are a number of enigmatic things about the Blue Book. The loss of files and institutional knowledge between when the list was first made in the 1920s and when it was published in 1966 means we have to do our best to reconstruct some pieces of the puzzle.”

Names repeat. Records are lost. People move. And whakapapa, while grounded in ancestry, is also shaped by place, community and lived relationships.

“In a tikanga Māori way, your whakapapa takes you to each marae,

each hapū that acknowledges an ancestor,” Joseph says. But under colonial frameworks – like rūnanga constitutions – those ties can be excluded.

“For example, my mum owns land and was raised at Arowhenua,” says Joseph. “But she can’t register there. Under a tikanga Māori perspective she belongs, but under the constitution she can’t participate in the electoral process.”

Still, the Blue Book has immense value. It’s not just a list of names, it’s a statement of survival.

“Even today, those books – especially the Blue – are constantly used to assist individuals and whānau looking for their Ngāi Tahu links,” says Muriel. “And if no whakapapa links them to us, that Blue Book can help them find their own rūnaka of belonging.”

It’s not perfect, but it endures. Ultimately, the Blue Book stands as a legacy and a living document. Born in a colonial context, but carried forward by generations of Ngāi Tahu, it’s a product of compromise and a symbol of perseverance.