The first language of Te Waipounamu

Apr 5, 2015

Rock art is one of the oldest and most significant of the traditional arts, and considered by some an early form of written language.

Kaituhi Nic Low reports.

Archaeologists Brian Allingham and Julie Brown have a great commute to work. They leave Timaru for the winding river gorges of Ōpihi and Pareora, travelling inland, westwards, on routes once walked by foot. It is ancestral country out here. Moa bones turn up in the swamps. Shoals of limestone rise from pastureland on all sides. The stone is soft, receptive to water and wind, and riddled with caves. It’s home to the most intriguing of Ngāi Tahu taonga. Almost every outcrop around here is marked with priceless rock art.

At Hanging Rock bridge someone has sprayed the sign with buckshot. We go from tar-seal to dirt track to a field of head-high corn. The Ngāi Tahu Māori Rock Art Trust truck pushes through like a miniature combine harvester.

“This is nothing,” Brian laughs. “First time we came here it was generations of blackberry. Took hours to slash our way through.”

We’re at location S102/38. The old name of this place is lost, and there are so many sites where the ancestors made their mark – 600 found so far – that plenty are known only by a number.

We leave the truck and descend into a small gully dotted with tī trees. A deep overhanging ledge of limestone cuts back into the hillside. It faces south, sheltered from the nor’west wind and rain. A small stream runs through the centre of the gully. It’s a perfect campsite.

“It’s genius art. It’s a huge story, with this enormous scale and complexity.” Brian Allingham Archaeologist

Beneath the overhang, our eyes take a while to adjust. Then, like a Magic-Eye picture coming into focus, it’s right there: a vast fresco of tiki, kurī, manu, spirit creatures, and koru forms; all rendered by careful hands in charcoal blacks and ochre reds. A man holds a kurī high above his head. Other dogs stand alert. Their heads and tails curve like the prow of waka. I lie back on the earthen floor and take it in. Stunning.

Beneath the overhang, our eyes take a while to adjust. Then, like a Magic-Eye picture coming into focus, it’s right there: a vast fresco of tiki, kurī, manu, spirit creatures, and koru forms; all rendered by careful hands in charcoal blacks and ochre reds. A man holds a kurī high above his head. Other dogs stand alert. Their heads and tails curve like the prow of waka. I lie back on the earthen floor and take it in. Stunning.

“It’s genius art,” Brian says. After 25 years working in the field he has intimate knowledge of the broad districts, the individual caves, the specific figures. His tanned, grinning face is filled with love for the form. “It’s a huge story, with this enormous scale and complexity.”

Rock art is one of the oldest and most significant of the traditional arts, and considered by some an early form of written language: meaningful marks left for others to read. Some of those marks offer a glimpse of the world in the time of moa and pouākai (Haast’s eagle). Earlier that morning I’d witnessed a drawing of the giant eagle soaring across a cave roof at Frenchman’s Gully. In this landscape of hawks and falcons, it’s easy to imagine the artist looking up to see that vast shadow pass above.

Then there are taniwha and manaia, sailing ships and Roman script. Most intriguing of all are the bird-people. They have human bodies, their arms outstretched like wings, with lines of small birds perched upon their shoulders. They survey their brothers and sisters with the enigmatic faces of birds. Who or what are these creatures? Who drew them – Rapuwai, Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu? How long ago? What do they mean?

“It’s like an ink-blot test,” says Amanda Symon, archaeologist and curator at Te Ana Ngāi Tahu Māori Rock Art Centre. “What you see says more about you than the work.”

A reluctance to offer interpretation is understandable. Since the mid-19th century, surveyors, ethnographers, and archaeologists have all offered opinions as facts.

“Every time you think you’ve got a pattern, you find something that contradicts it,” Brian says.

Even questions about the exact age of the drawings come up cold. Radiocarbon dating on charcoal pigment pinpoints when the original tree died, but not when it was burned, and certainly not when it was employed as an art material. Some tests return ages of 4000-6000 years, suggesting not antiquity but contamination: in the 1940s artist Theo Schoon notoriously touched up many drawings with crayon

“It puts real ancestral meaning into decorative art. All those patterns, they’re all people, they’re all whakapapa.” Brian Allingham Archaeologist

What about oral histories passed down within the tribe? Last century, amateur historian James Herries Beattie asked Ngāi Tahu elders about the rock art traditions. He was told: “We don’t know what they mean.” Brian smiles at me.

“What that could mean is, ‘We’re not telling you.’”

So is it possible we’ll never know what our ancestors intended? Or could there be Rosetta Stones, key pieces of buried evidence that translate between their world and ours? Julie’s face lights up.

“Absolutely! There have already been a few.”

On the north bank of the Ōpihi River near Hanging Rock, there’s a tiki figure which, within a single drawing, moves from a naturalistic depiction of a human figure into a series of abstract triangles and diamonds. It’s the missing link between this ancient figurative art, and all the abstract shapes used in tā moko, tāniko, and tekoteko.

“It puts real ancestral meaning into decorative art,” Brian says. “All those patterns, they’re all people, they’re all whakapapa.”

While the Rock Art Trust team always emphasises questions over answers, there are other trends. The sites tend to be in sheltered gullies and caves. The ones I visited were cool, still, and silent. It’s easy to imagine them as temples. But it seems they were very much living sites.

“You have sacred art, and the walls would have been tapu, and there would have been protocol around that – not leaning against it, or baring your buttocks – but the areas immediately adjacent were noa.” Brian hands me an umu stone, blackened with charcoal, reddened by fire. “We open up the ground beneath the art and we find hearths, middens, bones, all the stuff of everyday life.”

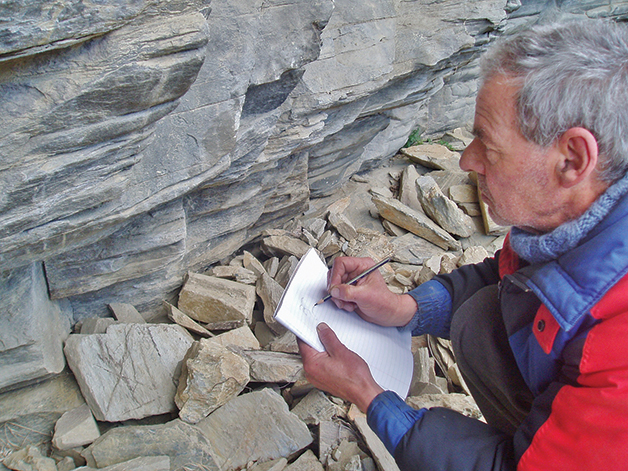

While we chat, Julie lays out a red and white tape, unfurls a sketch map and goes to work. Some of the figures before us are vivid, others ghostly. Here and there the story fades out entirely, lost to centuries of rain. At some sites graffiti artists, road workers, white supremacists, even the rasping tongues of livestock – licking salt from the limestone – have done irreparable damage. The Trust team’s goal is to find and record the totality of rock art in Te Waipounamu before further harm is done. They photograph, map, sketch, and digitally analyse each drawing. In 2014 the importance of their work was recognised internationally, with one of the world’s leading authorities on cave art, Dr Jean Clottes, visiting dozens of sites around the rohe.

“The rock art testifies to the beliefs, customs, and ceremonies of the Māori of old. As such it is an invaluable heritage,” Dr Clottes said.

“Brian Allingham and his team guided us to a number of sites. They have done a great job at finding, surveying and protecting them.”

“Feeding young minds is our way of getting a generation to grow up with this as part of their lives, as people who respect and appreciate the history we have in this art.” Jill Kitto Rock Art Trust chair and Te Rūnanga o Moeraki representative

Wendy Heath, Te Rūnanga o Waihao representative on the Ngāi Tahu Māori Rock Art Trust, was with Dr Clottes when he first saw the taniwha at Ōpihi. “When you stand alongside a rock art expert with a lifetime of experience, and watch his jaw drop in sheer wonder and hear his startled ‘wow!’, you know how truly amazing our tīpuna are.”

It’s not just European experts who come to appreciate the art. With the backing of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, Te Ana Māori Rock Art Centre in Timaru lets tourists, locals, families, and farmers access these taonga without the need to hack through blackberry.

“We get quite a few farmers coming in,” Amanda says. “The work’s almost all on their land, and many of them feel a strong sense of guardianship for the rock art sites on their properties.”

The other vital function of Te Ana is to let visitors see the art in the context of Ngāi Tahu tikanga, and through the eyes of the descendants of those who created it.

“Education has become a leading role for Te Ana and the Rock Art Trust,” says Jill Kitto, trust chair and Te Rūnanga o Moeraki representative. “Feeding young minds is our way of getting a generation to grow up with this as part of their lives, as people who respect and appreciate the history we have in this art.”

The guides at the centre are all young Ngāi Tahu. Wes Home has been at Te Ana since it opened. He talks us through the inland trails leading from the coast towards Aoraki, and some of the drawings along the way. One is a kiwi embryo, beautiful and ghostly as an ultrasound. Another from Maungatī shows a rare image of a tattooed face, meeting our gaze through the centuries. The original is so faint that it’s only visible on damp, misty days. Like much surrounding rock art, the face is fascinating but ambiguous, glimpsed and then lost.

“Often we go to show people,” Wes says, “and he’s gone.”

A Sense of Connection

When Brian Allingham began his training in archaeology, he wasn’t particularly interested in rock art. He’d seen a few 2D tracings of the designs, but what were they compared to dreams of digging up ancient pounamu mere? Then, as a young field worker, he found himself helping out on a rock art field survey. The work came to life. He saw the drawings as their creators had: inscribed on stone in caves and shelters among the hills of Te Waipounamu. Brian has been working with rock art ever since, leading archaeological digs, liaising with local rūnanga, publishing articles, and most of all, spending more than two decades working with rock art in its natural element.

In the early 1990s Brian, Atholl Anderson and Gerard O’Regan launched the South Island Māori Rock Art Project (SIMRAP). The Ngāi Tahu rohe was divided into blocks based on river catchments. Then, each and every limestone formation was investigated on foot, kilometre by kilometre. The number of known sites jumped by 300%, with much work still left to do.

As well as documenting the art, a key goal was to bring it into the lives of tribal members. A pivotal moment was when several vanloads of Ngāi Tahu whānui visited places no Ngāi Tahu had seen in more than a hundred years.

“I could see people moving from a theoretical valuing of the art to an actual experience of it and feeling empowered by this,” writes Gerard in Being and Becoming Indigenous Archaeologists (edited by George Nicholas). “It crystallised my thoughts that in order for people to meaningfully assert authority over our treasures, they first had to know what and where those treasures are, and also to actually experience them.”

It was this experience of witnessing the art in situ that first moved Wendy Heath, Te Rūnanga o Waihao representative on the Ngāi Tahu Māori Rock Art Trust. “The first time I saw rock art in the field it was at Takiroa in the Waitaki Valley. I was struck by a sense of connection to the place and the art. The evocative nature of these figures and symbols call to us all in different ways, but for me it was the sure knowledge that our tīpuna walked these sites and left these stunning, complex, and powerful reminders of their presence.”

The trust was formed to support papatipu rūnanga and their communities in the care, management, and interpretation of rock art. Protection is particularly important, given the work’s fragile nature and constant exposure to the elements. Only a handful of the 600 known sites are actively managed and protected.

“The Rock Art Trust aims to protect the art through recording, photographing, and detailing their whereabouts,” says Jill Kitto.

“Along with preservation, in some areas [our work is] fencing, liaising with private landowners on the significance of these pieces of art, and encouraging their involvement by keeping stock and stock feed out of these areas. Irrigation has become an increasing problem with the over-irrigation of land for dairy.”

The trust also works hard on engaging both Ngāi Tahu and the general public. School and marae programmes teach kids about their local heritage, while the landmark Te Ana Māori Rock Art Centre is a tourist attraction of national significance. Interactive exhibitions, hands-on drawing activities, and virtual tours sit alongside tribal traditions, mahinga kai, and introductions to the complex relationship between land, colonisation, farming, and the loss of access to rock art sites. For those wanting to experience the art on its natural canvas, Te Ana offers rock art tours with local Ngāi Tahu guides. There’s a discount for Ngāi Tahu members, and proceeds go towards preserving rock art for future generations.

A sense of time, place and people. How the passion to preserve rock art gathered momentum.

Kaituhi David Slack reports.

“People were out there in the shelters looking at the rock art with Brian Allingham,” says Gerard O’Regan, “and his contagious enthusiasm just rubbed off. It got those folk really excited.”

He’s speaking, over coffee in an art gallery, of an exciting time. Ngāi Tahu was taking a claim to the Waitangi Tribunal. Gallery visitors across the world had recently been enthralled by Te Māori.

It was a time of reclaiming cultural authority over taonga. Now Ngāi Tahu was about to take an active role in recording, preserving and managing rock art.

The Canterbury Museum had for a long time been the focal point of rock art research. Former director Roger Duff had been involved with surveys by the artists Theo Schoon and Tony Fomison. Another former director, Michael Trotter, along with Beverley McCulloch published what is still the most authorative text on the subject, Prehistoric Rock Art in New Zealand.

However, Gerard says it was generally accepted that South Island rock art was incompletely recorded, and much of it unprotected. “People recognised that we really need to go back and revisit a lot of the sites.”

Brian Allingham and Atholl Anderson picked up that challenge. Brian had been active in archaeology in Otago and Canterbury, working with rock art. Atholl (Ngāi Tahu) lectured in archaeology at the University of Otago.

Brian Allingham did a pilot survey. The results showed there was much more rock art out there – in some places three times more than had previously been known of.

“When he got those results there was absolute recognition – by the Historic Places Trust [now Heritage New Zealand] – by all the archaeological fraternity involved in rock art – that we needed to do a separate survey again. But of course everyone was too busy and no-one had the time to do it.”

A hui of tribal representatives was called, convened by Atholl Anderson. And that was how they came to be out there in the shelters that day, looking at the rock art with Brian Allingham.

“We convened back for a cuppa at the Duntroon pub,” Gerard remembers. The hui had the effect of galvanising “the enthusiasm that Brian had imparted for the rock art, the recognition of how fast this stuff was deteriorating, and just what was actually there and the kinds of questions we could ask about rock art.”

And here, Gerard became involved.

“I’d just gone along for the field trip, and to enjoy the scenery and the discussion and the whanaungatanga. When the question came up who would manage the project in Atholl’s absence [he was leaving for Australia], Atholl kindly volunteered me for it, and it was all – in typical Māori fashion – approved and accepted, signed and sealed without really asking. I wasn’t in a position to say no.”

The first steps were small. “The Historic Places Trust put funding into it which allowed Brian to keep a little bit of petrol in his truck for a while. At times we had no money and Brian would go and do a contract job, and make a little bit of money, which gave him enough petrol to go and do another couple of weeks in the field. He lived on a shoestring, and a lot of that earlier work was really voluntary.”

Momentum gathered. “Rock art is incredibly visual. On tribal hui, we could actually take people to visit them. It provides that wonderful sense of connection with a place. Whānau who were on those visits became quite strong advocates for the rock art kaupapa back on their marae.”

Brian and Gerard developed a full project proposal, and presented it to the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, and to a tribal hui-ā-tau.

“I remember one kaumātua standing up and saying, ‘I think this is a great job. We ought to do it and we ought to pay for it.’” The chief executive looked aghast, he remembers, but it was adopted.

It was proper funding bolstered greatly by ECNZ (now Meridian) and the Lotteries Commission that enabled them to undertake the long-term project that SIMRAP has become. The project is ongoing.

Gerard is excited by the prospect that future generations will interpret the rock art, deal with it and incorporate it into their work – perhaps even reigniting the practice of traditionally marking the land.

“I look at it very much in the way te reo revitalisation has enriched Te Ao Māori. Or the taonga puoro that you hear all over the place now – that goes back to Richard Nunns and Hirini Melbourne doing research in the museum collections, seeing what sounds were potentially able to be drawn out of these instruments, and researching to find what is within the reasonable scope and what isn’t for Māori music. Undoubtedly they’ve stretched some boundaries, but we now have this re-emergence of those sounds in our contemporary world, enriching our contemporary lives, but with that there is also a sense of a connection back into the past.

“There’s a long history of re-use of rock art. Different people in Ngāi Tahu have been re-using rock art imagery in other media. In the kōwhaiwhai panels in meeting houses, in the bodices of the historic Ārai Te Uru kapa haka group, and more recently, whānau who have incorporated rock art motifs in their tā moko.

“When discussions come up around rock art and its protection and care, because of the reuse, it’s quite near to the discussion already.”

People, when they talk about the rock art, will ask, “What does the rock art mean?” They are usually thinking about when the artist created it. What’s equally important, Gerard argues, is how people over time have engaged with and responded to that rock art and its places, and how they are still doing so.

“There are multiple audiences engaging with the rock art in a whole variety of ways, some from an educational point of view, some others taking artistic inspiration, others – marae for example – relating to them in terms of a wider relationship back to the landscape and the mahinga kai and so on.”

When we talk about rock art, Gerard says, place, time, and people matter just as much. “It’s not just the art.”